| “I think it's fine for a scientist to prefer to work on things that they personally agree with as long as they maintain their objectivity and as long as they respect other scientists' right to work on what that person agrees with. I think working on prosociality can make it more difficult to maintain those distinctions.” |

| “I've never really thought about the fact that I default to causes that I support personally in my stimuli. I mostly stick to relatively non-controversial causes (my research is in the arts), but the question and potential bias is good to have in the back of my mind.””, ““I think that any bias against research supporting a cause I disagree with would be unintentional (although likely still present). I'm less sure about that being true for everyone (although hopefully true for most other researchers!).” |

| “The valence of a paper about a cause people oppose matters in the previous questions. If the paper were an outright advocacy piece, that would be met more harshly. However, if it were objective and explored the motivations/deterrents in a balanced manner that could be evaluated differently - especially as a job market paper where the candidate had an opportunity to explain the reason for selecting a particular cause” |

| “When I was answering I had in mind the NRA. So even though I really try to not be biased against people / researchers based on their political opinions, especially since we have such a liberal bias in academia, I found that I could not give any other answer than the ones I have given. I simply would not be able to judge positively research done on charity donations to the NRA. However, I also don't think there exist many researchers, conservatives or otherwise, who would attempt it.” |

How Political Ideology Shapes Prosocial Consumer Behavior Research

The current research suggests that there is a lack of political diversity in the stimuli used in prosocial consumer behavior research, which may pose challenges for the reliability and generalizability of such work. We review prosocial consumer behavior research from the leading marketing journals across twenty years and show that the study stimuli therein exhibit a consistent liberal skew. In a survey of contemporary prosocial consumer behavior researchers, we identify that the political beliefs of researchers and bias against conservative cause areas likely explain the observed political skew of stimuli in prosocial consumer research. Finally, three lab studies (N=2,008) demonstrate that unacknowledged political valence of prosocial stimuli and the unmeasured political beliefs of participants can distort estimates of the relationship between individual differences and donation if not accounted for in a thoughtful manner. This work contributes to the literature on prosocial consumer behavior by identifying a bias in stimuli selection that has likely hampered our understanding of the full nature of prosocial consumer behavior.

Prosocial Behavior, Political Ideology, Charitable Giving

Introduction

“I live in a Republican congressional district in a state with a Republican governor. The conservatives are definitely out there. They drive on the same roads as I do, live in the same neighborhoods. But they might as well be made of dark matter. I never meet them.” — Dr. Scott Alexander (2014), excerpt from “I Can Tolerate Anything Except the Outgroup”

Conservatives give as much, if not more, to charity than liberals. This finding is consistent across national surveys of consumers (Margolis and Sances 2017), meta-analyses of prosocial behavior research (Yang and Liu 2021), and analysis of county-level tax filings (Paarlberg et al. 2019). However, the considerable extent of conservative charitable giving has had surprisingly little impact on prosocial consumer behavior research, which typically focuses on more liberal cause areas like environmental conservation or politically neutral cause areas like cancer research. Traditional conservative cause areas, such as religious institutions or veterans’ charities, receive very little attention in the literature. To the extent that political conservatism is considered, usually in the form of an individual difference or demographic measure, it is often examined with the goal of motivating conservatives to donate to liberal causes (Kaikati et al. 2017; Kiju et al. 2017). We argue that if conservatives represent a similar proportion of the population and give as much (or more) to charity as liberals, then the lack of conservative causes in experimental stimuli may limit the generalizability of prosocial consumer behavior research. The goals of this research are to 1) assess the extent to which contemporary prosocial consumer behavior research is skewed towards investigations of liberal and non-partisan causes (and away from conservative causes), and 2) investigate the extent to which this skew in stimuli may limit the generalizability and accuracy of contemporary prosocial consumer behavior research.

Across five studies employing multiple methodologies, we identify the extent to which liberal causes are overrepresented in prosocial consumer behavior research, explore mechanisms contributing to this overrepresentation, and provide evidence that this overrepresentation can meaningfully distort effect-size estimates. Specifically, we show that conservative stimuli are highly underrepresented in prosocial consumer behavior research published in premier marketing journals. We then explore whether the focus on liberal and non-partisan causes may be connected to the political ideology and cause preferences of prosocial consumer behavior researchers. The absence of conservative cause areas as stimuli is not inherently problematic for any individual paper per se, but we demonstrate both theoretically and empirically that bias in stimuli selection risks artificially accentuating or attenuating estimates of the effects of individual traits that are correlated with both political beliefs and prosocial consumer behavior.

The current work contributes theoretically and practically to the prosocial consumer behavior literature in several ways. Theoretically, an omission of conservative stimuli may result in missed opportunities to better understand the conceptual underpinnings of the donation behavior of conservative donors–who are likely morally, motivationally, and temperamentally distinct from liberal donors. We build on existing research that focuses on the psychological differences between conservatives and liberals (e.g., Graham, Haidt and Nosek 2009), as well as the link between such differences to consumer donations (e.g., Winterich, Zhang and Mittal 2012), to suggest that a better understanding of the unique features of donations to conservative charities may allow researchers to both broaden the scope of motivations that can result in prosocial behavior, and more fully explore how political affiliation interacts with different types of charitable appeals. Practically, we provide several concrete recommendations for researchers to avoid issues that may arise from using only liberal stimuli. Importantly, we suggest researchers use charities representing a diverse range of moral and political values in their studies. However, in some cases where researchers are interested in particular cause areas with strong political valence (e.g., environmental conservation), this recommendation is not feasible. We, therefore, show that measuring and controlling for the political valence of stimuli, as well as the political beliefs of participants, can mitigate concerns of politics confounding the relationship between individual differences and donation behavior.

Theoretical Development

Before outlining our theoretical framework, it is first important to clarify important terms. Specifically, what do we, and consumer research scholarship as a whole, mean by terms like “prosocial behavior” or “liberal” and “conservative”?

Definitions of prosocial behavior tend to be diverse (Pfattheicher, Nielsen and Thielmann 2022), in part because prosocial behavior refers to a broad set of behaviors that emerge from a diversity of situations, individual differences, and psychological processes (Batson 2022). We generally understand prosocial behavior to mean actions taken with the intent of helping others, often at some cost to the self (White, Habib and Hardisty 2019). In practice, however, we take researchers’ self-classifications of their own work as investigating prosocial behavior to be sufficient for categorizing consumer behaviors as prosocial.

Similarly, definitions of terms like “liberal” or “conservative” can be somewhat nebulous, with scholars arguing that these terms refer to between-group differences in moral foundations (Graham et al. 2009), beliefs about the moral significance of inequality (Bobbio 1997), or tendency towards supporting the status-quo (Jost et al. 2003). In the current research, when we say “liberals”, we mean those individuals who would identify as being liberal. Moreover, when we describe some charities as “neutral”, we mean those charities that have roughly equal support from both liberals and conservatives. In practice, this means that we defer to consumer judgments of themselves and charities as liberal or conservatives, without asking them to agree with a specific theoretical account of political beliefs.

A Liberal Skew in Stimuli

We propose that there exists a political skew in prosocial consumer behavior research such that liberal causes are overrepresented and, consequently, conservative causes are underrepresented. This skew is likely multiply determined but may be attributable to: 1) academics being primarily liberal and thus preferring research aligned with their interests, or on topics with which they have personal ties and connections to, 2) academic researchers tending to underexplore religion as a topic area, which represents a large fraction of conservative donations, and 3) conservatives donating to a more limited set of charities and thus using a broad range of prosocial stimuli may naturally result in a liberal skew. Formally,

H1: Prosocial behavior researchers will exhibit a preference for liberal stimuli.

Academics are Generally Liberal

We expect that prosocial consumer behavior researchers will tend to be liberal. Survey evidence from social psychology—a field with a high degree of overlap and cross-disciplinary collaborations among consumer and social psychology researchers—supports this supposition (Buss and Hippel 2018; Honeycutt and Freberg 2017; Inbar and Lammers 2012), as well as analyses of academics’ voting behaviors (Langbert, Quain and Klein 2016). To the extent that marketing researchers—and prosocial consumer researchers, in particular—are similar to social psychologists and the academy at large, then they are likely to be similarly liberal. We propose that this abundance of left leaning academics is likely to result in a liberal skew in prosocial consumer behavior stimuli for two reasons: academics’ preference for politically congruent charities, and academics’ skepticism toward politically incongruent charities.

Because academics tend to research subjects they have a personal connection to in other domains [also known as “me-search”; Altenmüller, Lange and Gollwitzer (2021)], we suggest that the same holds for academics researching prosocial consumer behavior. Specifically, we expect that prosocial consumer behavior researchers, who we expect are generally liberal, will use more politically congruent (i.e., liberal) charities as stimuli. The reasons for this stimuli preference are varied. For example, academics may: 1) wish to promote politically congruent charities, 2) ask research questions that require the use of more liberal causes, 3) be more aware of politically congruent charities and thus are more likely to select them as stimuli, and/or 4) have more pre-existing connections with politically congruent charities and thus have more access to data and information from such charities. Formally:

H2a: Researchers’ preference for liberal stimuli will be consistent with a preference for ideologically congruent charities.

We further propose that liberal academics may be more uncertain, uncomfortable, and/or skeptical about facilitating donations to conservative charities—which they may morally oppose. Such responses would, in effect, result in fewer papers on conservative cause areas and fewer researchers willing to investigate such causes. Importantly, we do not argue that this process is necessarily malicious but is, in fact, likely to be prosocially motivated (Clark et al. 2023).

While not directly explored in the context of prosocial consumer behavior, skepticism towards conservative values and subsequent omission of conservative perspectives is well-documented in the related fields of psychology and philosophy (Baumeister 2022; Duarte et al. 2015; Honeycutt and Jussim 2020; Inbar and Lammers 2012; Peters et al. 2020). Research on this topic in adjacent fields typically finds that ideological bias can result in a reduced number of conservative academics investigating cause areas they care about and poses barriers to the publication of papers that investigate conservative cause areas. Formally:

H2b: Researchers’ preference for liberal stimuli will be associated with a reduced preference for ideologically incongruent charities (conservative stimuli).

Religion as a Neglected Cause Area

We further propose that a significant fraction of this skew will be attributable to neglect of religious institutions as vehicles for charitable giving. Surveys by “Pew Research” (2024) suggest that conservatives currently have a closer connection to religion relative to liberals on a variety of dimensions, including: belief in god (“absolutely certain”: 78% of conservatives, 45% of liberals), importance of religion (“very important”: 70% of conservatives, 36% of liberals), service attendance (“at least once a week”: 50% of conservatives, 22% of liberals), and using religion as a moral guide (“look to religion most for guidance on right or wrong”: 50% of conservatives, 18% of liberals). A neglect of religious donations in the prosocial consumer literature would, therefore, disproportionately impact representations of conservative perspectives, which is especially troubling given that religiously motivated donations represent the largest source of donations made in the United States (Giving USA 2023).

We, specifically, propose two reasons that a neglect of religious donations is likely: 1) a reliance on lab-based paradigms in prosocial consumer behavior research, and 2) secularism in the academy. We address each in turn below.

Lab-based paradigms. Consumer research, and especially prosocial consumer behavior research, tends to primarily use lab-based paradigms. Consequently, prosocial behavior researchers are directed towards utilizing and developing theoretical frameworks that are amenable to experimental analysis in the lab. Penner et al. (2005) conceptualize prosocial behavior frameworks as operating at meso (situational—e.g., the empathy-altruism hypothesis: Batson and Shaw 1991; hedonism and egoism: Cialdini et al. 1987), micro (development of prosocial tendencies—e.g., personality approaches: Ashton et al. 1998; Thielmann, Spadaro and Balliet 2020; cognitive learning: Bar-Tal 1982), and macro levels (organizational—e.g., Penner 2002; Wilson 2000). Importantly, whereas religiously motivated prosocial behavior often occurs at an institutional level (macro), prosocial behavior research typically only considers meso- and micro-level frameworks for prosocial behavior, as it is relatively easy to experimentally alter situational conditions (meso; e.g., experimentally varying the perceived efficacy of a charity) and include individual differences as moderators (micro; e.g., measuring trait-empathy) in the context of a lab study. By contrast, understanding how giving occurs at a macro level within institutions would likely involve—and indeed, has involved (Penner 2002)—surveying individuals already embedded within such institutions. Targeted surveys of this sort are more logistically challenging to conduct than surveys of online convenience samples and consequently less attractive for researchers who have limited time and funds with which to conduct research. We should, therefore, expect a natural neglect of religiously motivated donations in consumer research, because of prosocial consumer researchers’ methodological and theoretical commitments.

Secularism in the academy. We also propose that because academics tend to be more secular than the broader public, they may, therefore, be less interested in investigations of religious phenomenon (Research 2009). Prior research in the adjacent field of sociology suggests that sociological explorations of religion tend to be marginalized, because researchers who conduct such explorations are themselves labelled “religious” or “conservative” and subsequently treated as less rigorous, interesting, or needed in departments (Perry 2023). We propose that prosocial consumer researchers, as a broadly secular cohort, will have less experience with religiously motivated donations and thus are likely to under-research such phenomena. In other words:

H3: Religious based donations will be underrepresented compared to liberal and non-partisan donations.

Charity Diversity

One alternative explanation for the bias we predict is the relatively concentrated nature of conservatives’ charitable giving. While conservatives may give more overall to charity, they tend to donate to a smaller set of charities than liberals (Margolis and Sances 2017; Yang and Liu 2021). This aligns with the demographics of the broader pool of US charities, of which there are more liberal than conservative charities. Estimating this skew is difficult, but text analyses of US non-profit IRS filings suggest that upwards of 80% of all US non-profits express sentiments more consistent with liberal than conservative values (Han, Ho and Xia 2023). If the pool of liberal non-profits is larger than the pool of conservative non-profits, then an alternative explanation for our hypothesized liberal skew in stimuli may be that papers which include a wide range of stimuli will naturally include more liberal cause areas. If the greater diversity of liberal charities explains our hypothesized skew in stimuli, we should then expect that papers which include more stimuli will end up selecting more liberal organizations. Formally:

H4: Papers with a greater (vs. lesser) number of charitable stimuli will be associated with increased (vs. decreased) liberal skew.

However, should we find that papers with more stimuli do not ultimately select more liberal causes, then this would be evidence against a stimuli diversity account and rule out an alternative explanation for our hypothesized bias in the literature.

Why Political Over- (and Under-) Representation Matters

Concern about political overrepresentation may be warranted, as political, moral, and ideological biases across the political spectrum have arguably hindered research in a variety of other areas, including: left-wing authoritarianism (Costello 2022), misinformation (Enders et al. 2022), open science (Uygun Tunç, Tunç and Eper 2022), microaggressions (Lilienfeld 2017), intelligence research (Harden 2021), pornography addiction (Grubbs and Perry 2019), violence and video games (Ferguson 2007), criminal justice (Savolainen 2023), and evolutionary psychology (Mackiel, Link and Geher 2023). Prosocial consumer behavior research is similar to these other areas in that the topic involves strong beliefs on the part of researchers and consumers as to what is “good” and is, therefore, particularly susceptible to partisan biases.

We propose that liberal overrepresentation (and conservative underrepresentation) may be problematic for prosocial consumer behavior research because: 1) overrepresentation results in incomplete frameworks that neglect unique moral and psychological characteristics of conservatives, and 2) a combination of politically homogenous stimuli (e.g., all left leaning stimuli) and unmeasured political beliefs of participants may erroneously inflate or deflate the effect of certain individual differences on donation. We expand on each in turn.

Incomplete frameworks. Because prosocial consumer behavior is fundamentally concerned with what constitutes “doing good”, political and moral concerns will be highly relevant to many donation decisions. Liberals and conservatives often differ in the values and beliefs that guide their determination of what is best for society and are also morally different from one another (Graham et al. 2009). Similarly, many charities vary with respect to the moral and political beliefs they activate (Goenka and Osselaer 2019). An absence of conservative cause areas would, therefore, be concerning as it may result in missing how conservative values uniquely influence prosocial behavior, as well as potentially feeding conservative concerns that academia is fundamentally biased against conservative beliefs.1

For example, Goenka and Osselaer (2019) demonstrate that congruency between emotions conveyed in charitable appeals and an organization’s moral mission can result in increased donations. In practice, this means that organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union, which are concerned with justice, activate the moral foundation of fairness and are, therefore, best served by appeals to the emotion of gratitude (versus care-oriented emotions like compassion). However, Goenka and Osselaer (2019) only focus on the two “individualizing” foundations of morality (e.g., care, fairness) that tend to be endorsed by liberals and omit the three “binding” foundations of morality that tend to be endorsed by conservatives [e.g., loyalty, authority, purity; Graham et al. (2009)]. Prior research has shown that this difference in moral foundations between liberals and conservatives can influence donation decisions (Winterich et al. 2012), but our understanding of how binding foundations interact with particular emotions to increase donations—as Goenka and Osselaer (2019) convincingly showed for the individualizing foundations—remains incomplete. Could such results be replicated for other moral/emotional pairings such as purity and disgust, authority and respect, or loyalty and patriotism?

Erroneous inflation and deflation of individual differences. All participants have political beliefs, and these political beliefs are correlated with a variety of individual differences. For some traits, it is obvious: Right-Wing Authoritarianism is correlated with conservative beliefs, such as favouring immigration restrictions (Peresman, Carroll and Bäck 2023), and Left-Wing Authoritarianism is correlated with liberal beliefs, such as favouring economic redistribution (Costello et al. 2022). For other traits, the associations are subtle, yet nevertheless relevant. For example, Just World Belief tends to be associated with conservative beliefs (Bénabou and Tirole 2006), and trait-empathy tends to be associated with liberal beliefs (Hasson et al. 2018).

The correlation of political beliefs with individual differences poses a problem for prosocial consumer behavior research that uses politicized stimuli. Without measuring participants’ political beliefs, researchers cannot know whether the relationship between some individual differences and donations to politicized charities is attributable to 1) the individual difference, 2) congruence between participants’ political beliefs and the politics of the charity, or 3) some combination of the two. In other words, the unmeasured political beliefs of participants can confound the effects of some individual differences (e.g., those correlated with political beliefs) in the presence of politically homogenous stimuli.

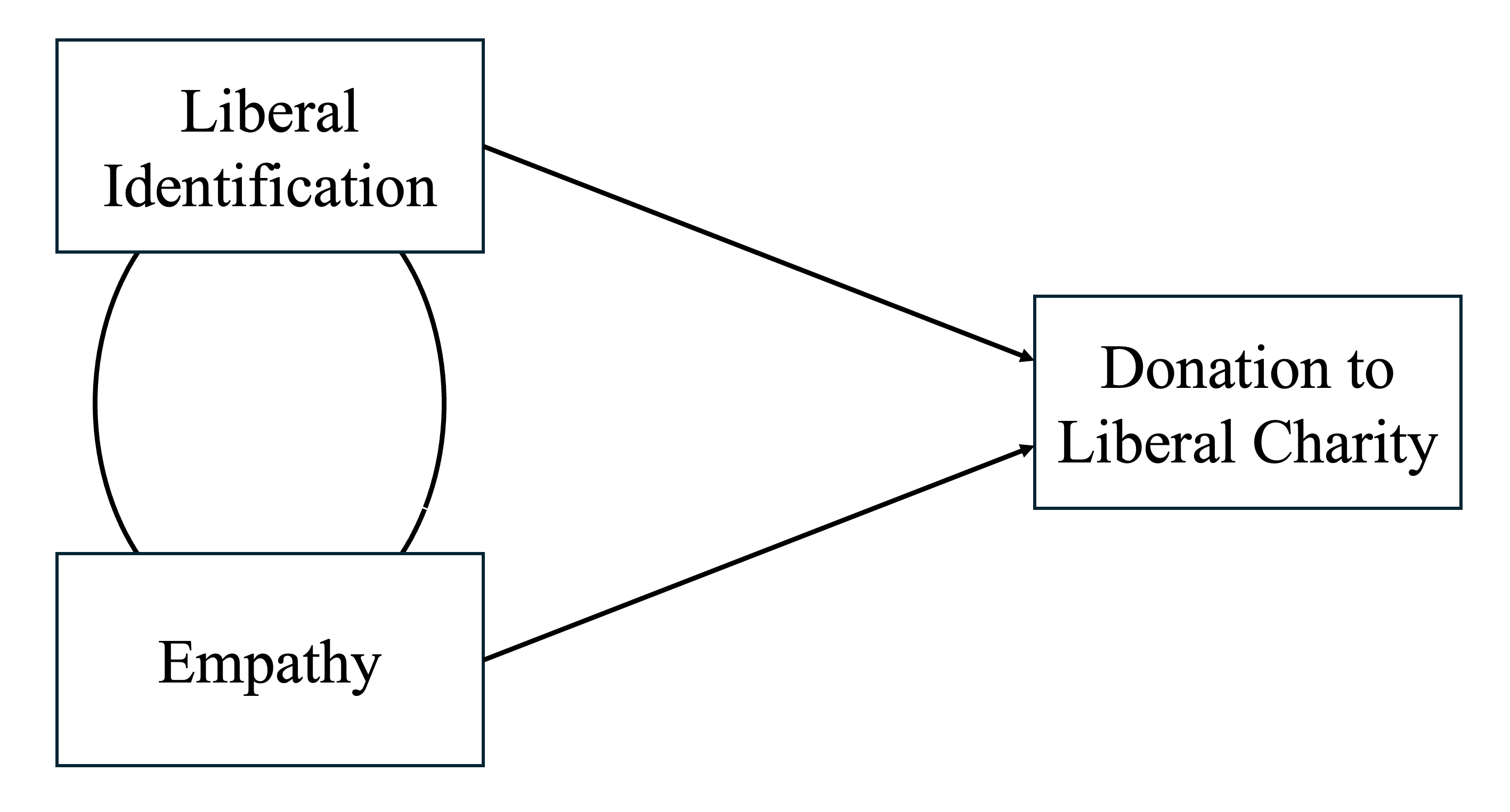

We depict a simplified version of a hypothetical relationship between trait-empathy, left-wing identification, and donations to liberal charities in Figure 1 to illustrate the problems that such unacknowledged confounding can have for causal inference. Empathy and liberal identification are correlated, and this relationship is plausibly bidirectional; empathetic people may be more liberal as a result of their empathy, and liberal people may experience greater motivation to be empathetic towards others to be consistent with their ideological beliefs (Hasson et al. 2018). Therefore, if only empathy and donation to liberal charities are measured, it is unclear whether any observed positive effect of empathy on liberal donations is attributable to empathy alone or also to liberal political beliefs that would be congruent with the liberal charity.

This confound can both erroneously inflate and deflate effects of individual differences on prosocial behavior in studies that utilize homogenous political stimuli. For individual differences that are associated with incongruent stimuli, their estimated effect may be suppressed; for individual differences that are associated with a congruent set of political beliefs, their estimated effects may be exaggerated.

However, even when participants’ political beliefs are measured, politically homogenous stimuli may still distort effect estimates by functioning as a hidden moderator. For example, consider the proposed negative relationship between authoritarianism and prosocial behavior (Costello et al. 2022). Suppose an individual high in Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) was shown a charity that promised to help immigrants. It is unlikely that this individual would feel particularly generous in this context, given the high correlation between RWA and antipathy towards immigrants (Peresman et al. 2023). By contrast, suppose this individual was shown a charity that promised to fight against immigration or other social causes they dislike. It may be that high-RWA people would be more charitable in such a situation. We argue the second case would serve as a more realistic test of the effect of RWA on charitable giving by providing high-RWA individuals with donation options consistent with their moral and political beliefs.

In other words, the political valence of stimuli may function as a hidden moderator that erroneously inflates some effects and erroneously deflates others. More concretely: an overrepresentation of liberal stimuli and a corresponding underrepresentation of conservative stimuli means that liberal participants will be presented with far more politically congruent donation options than conservative participants. Consequently, the effects of individual differences associated with conservative political beliefs may be deflated, whereas the effects of individual differences associated with liberal political beliefs may be inflated. For these reasons, we expect that politically homogenous stimuli will pose problems for rigorous estimation of the effects of certain individual differences on donation behavior. Formally:

H5: The effect of individual differences on prosocial behavior will be confounded (e.g., artificially inflated) when individual differences and stimuli are politically congruent.

Overview of Studies

Using a multi-method approach, we present five studies that empirically investigate these hypotheses. In study 1, we tested whether contemporary prosocial consumer behavior stimuli exhibit a political skew (H1); whether religious cause areas were present among these stimuli (H3); and whether our hypothesized political skew could be explained by papers with higher stimuli counts (H4). In study 2, we surveyed prosocial consumer researchers to identify whether our hypothesized political skew could be explained by their political preferences (H2). In study 3, we demonstrate that the political valence of stimuli can serve as a hidden moderator for the effect of politically correlated individual differences on donation (H5). Finally, in studies 4a and 4b, we demonstrate that political ideology can confound analyses estimating the effect of politically correlated individual differences on politicized stimuli (H5).

Study 1

The purpose of study 1 was to assess the state of contemporary prosocial consumer behavior research with respect to the political skew of stimuli. To that end, study 1 involves participants rating the political valence of charitable cause areas represented in contemporary prosocial behavior research. We next describe the process of constructing this set of cause areas.

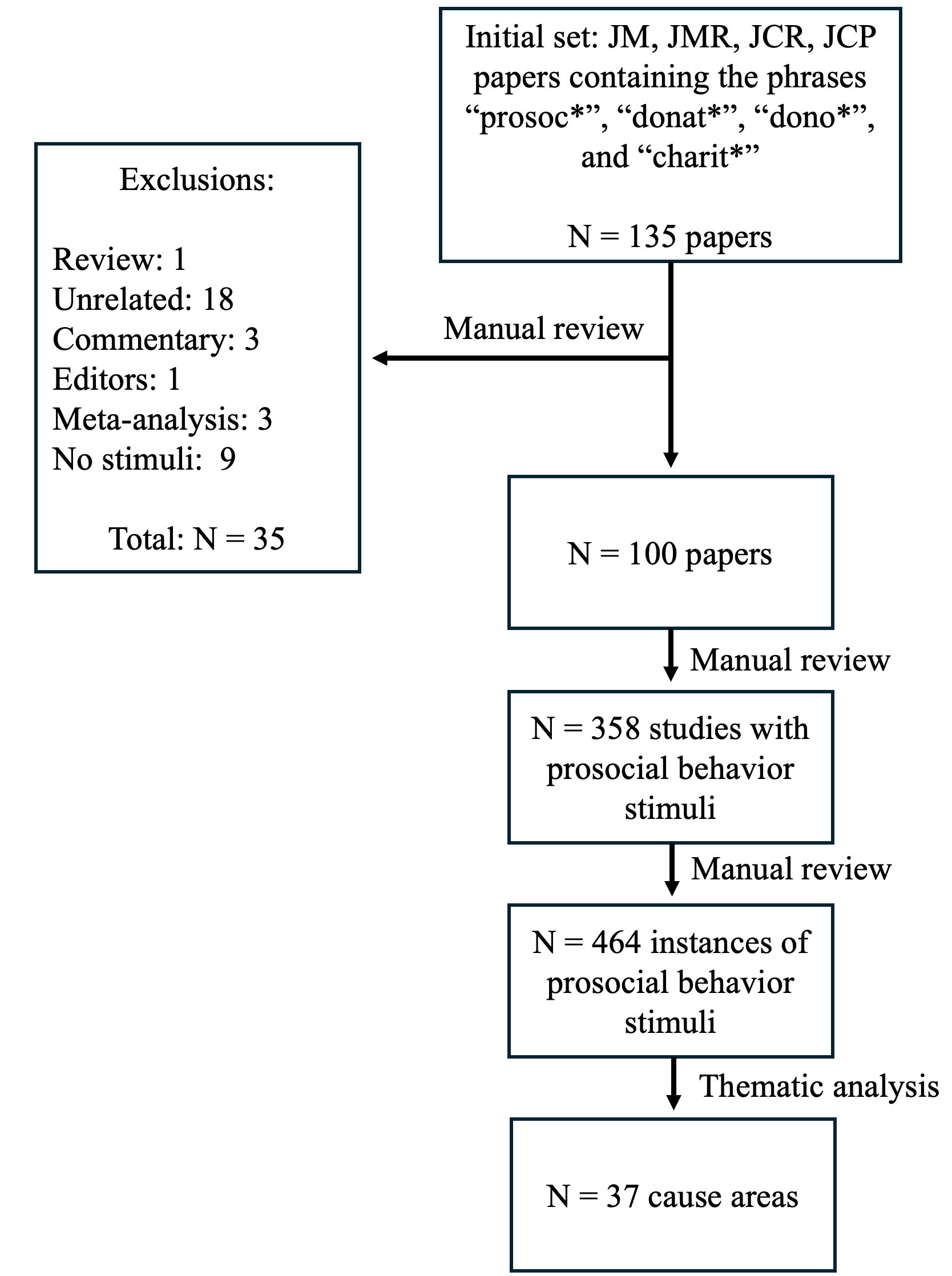

To construct our list of cause areas, we first reviewed all papers published since 2002 in four leading marketing journals—Journal of Marketing Research, Journal of Consumer Research, Journal of Marketing, and Journal of Consumer Psychology. We searched for papers with the strings “prosoc*”, “donat*”, “dono*”, or “charit*”, to identify an initial set of 135 papers that focused on prosocial consumer research. We excluded 35 review papers, commentaries, and other articles that ultimately did not investigate prosocial consumer behavior (such as papers about unrelated topics written by professors with named chairs referencing prosocial behavior), resulting in a final set of 100 papers. Of this set, we identified 358 studies that used a total of 464 different examples of charitable cause areas and organizations as stimuli. We then grouped similar cause areas and organizations together based on a qualitative thematic analysis—for example, donations to an Alzheimer’s charity and a Cancer charity were grouped under a broader “Health” category. This approach resulted in a final set of 37 unique cause areas (see Figure 2). This list then informed the subsequent empirical investigation we describe below. For a list of all papers included in our sample, as well as the codes generated for each study, see supplementary web appendix A.

Method

CloudResearch Connect participants (N = 200) completed a 38-factor (37 observed prosocial consumer behavior cause areas, plus donating to religious institutions) within-participants study in exchange for monetary compensation. We specifically balanced our sample between self-identified Republican (N = 103; 51.5%) and Democratic voters (N = 97; 48.5%). Our sampling technique addresses concerns that participants may perceive their political ingroup and related causes as systematically more prosocial than their political outgroup’s causes.

Participants were asked to rate each cause area on a 7-point scale (1 = “Very liberal”, 4 = “Neither liberal nor conservative”, 7 = “Very conservative”). For each cause area, participants were given the name of the broader category (e.g., “Indigenous rights”) and one stimuli example from our dataset (e.g., “donating to a Native American rights fund”). Participants’ ratings for each cause area were then averaged within and between political affiliations, as well as merged with our broader dataset to identify the overall political skew of stimuli across all papers.

Results

Our presentation of results is organized as follows: First, we assess participants’ ratings of the political orientation of each cause area in our dataset. Second, we evaluate the political valence of religious cause areas, which did not appear in our literature review but were included in our survey because of their importance in surveys of real-world donation behavior. Finally, we explore whether stimuli diversity is associated with the political skew we expected.

Analysis of Political Skew. First, we identified systematic differences between Democrats and Republicans such that each respectively believed that their in-group was more charitable2. Democrats rated the stimuli as more liberal (MRating = 3.26), while Republicans rated the stimuli as more conservative (MRating = 3.87; Δ = -0.61, CI95: -0.67, -0.56, t(906) = -20.37, p < .001). Nevertheless, with respect to overall perceptions of political skew, both Democrats (MRating = 3.26, CI95: 3.22, 3.29, t(463) = -37.82, p < .001) and Republicans (MRating = 3.87, CI95: 3.82, 3.91, t(463) = -5.69, p < .001) rated the stimuli in prosocial consumer behavior research as significantly below the scale mid-point and, therefore, identified stimuli as generally liberal. For simplicity, our analysis focuses on pooled ratings of Democrats and Republicans.

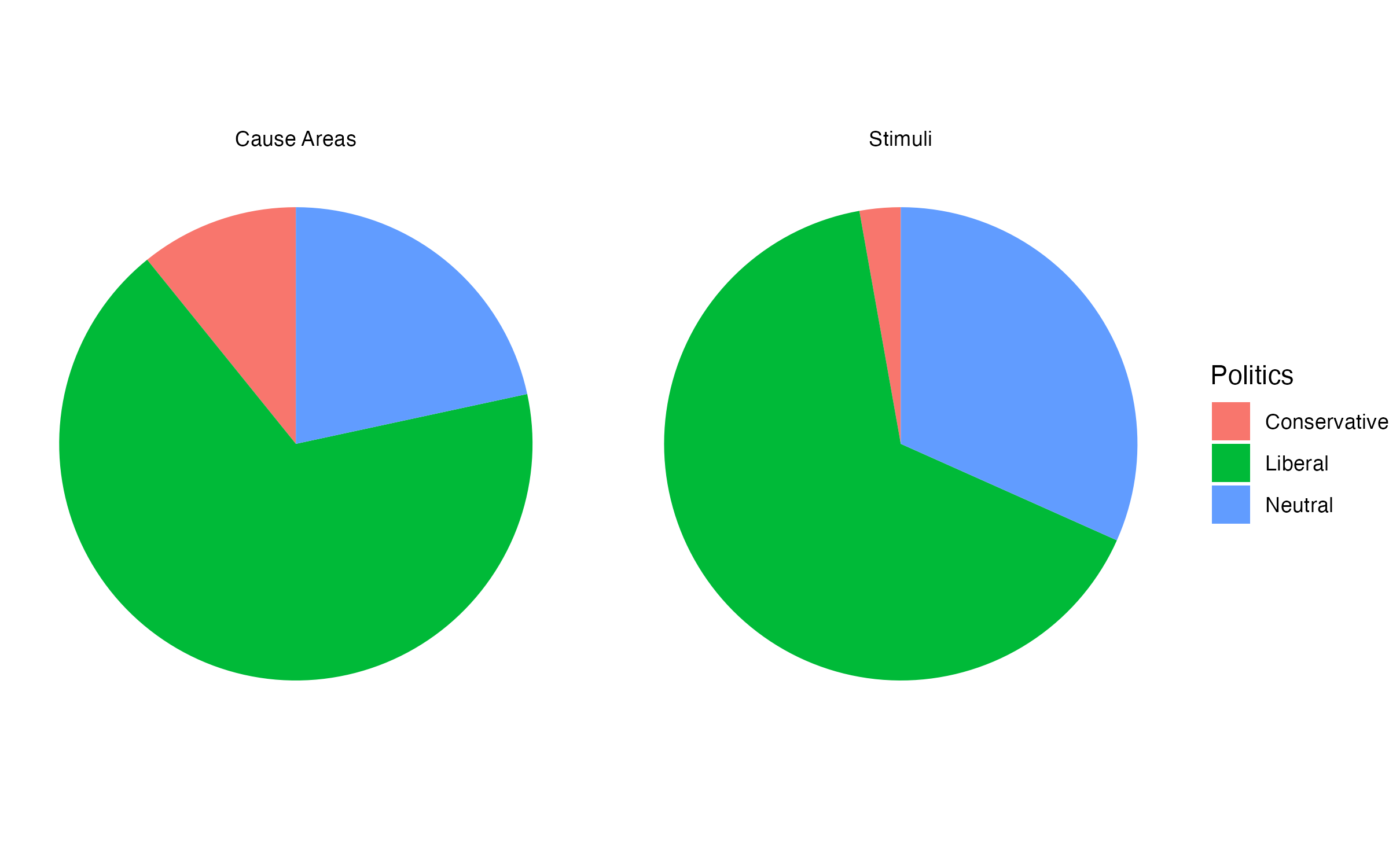

We then analyzed each of the 37 cause areas using a one-sample t-test to determine whether the average political valence for each was rated as significantly below the midpoint (liberal), significantly above the midpoint (conservative), or not significantly difference from the midpoint (neutral). Of the nndefineddefinedndefined37 cause areas, 25 (67.57%) were identified by participants as liberal, 8 (21.62%) were identified as politically neutral, and only 4 (10.81%) were identified as significantly conservative. However, some cause areas received more attention than others. Of the 464 prosocial stimuli identified in our data set, 65.52% (n = 304) were identified as significantly liberal; 31.68% (n = 147) were identified as politically neutral, and 2.8% (n = 2.8) were identified as significantly conservative. In other words, while 10.81% of all cause areas were conservative, their actual representation in terms of stimuli was much lower, at only 2.8%. The average rated political leaning across all stimuli in our sample was significantly below the scale midpoint (MRating = 3.57, CI95: 3.53, 3.61, t(463) = -20.91, p < .001), indicating an overall liberal skew for prosocial consumer behaviour stimuli (see Figure 3 & Figure 4)

Analysis of Religious Cause Areas. Stimuli and donations related to religious causes were absent in our review of contemporary prosocial consumer behavior literature. This finding is notable given that donations to religious causes represent the single largest area of charitable giving in the United States representing almost a third (29.11%) of all dollars donated (Giving USA 2023). Regardless, we included religious cause areas in our survey to confirm that donors do perceive them as more conservative leaning and to identify if their absence may be related to the liberal skew observed in our dataset. Overall, participants rated religious cause areas as more conservative than the scale midpoint (MRating = 5.65, CI95: 5.44, 5.87, t(199) = 15.51, p < .001), a result that was consistent across Democrat (MRating = 5.62, CI95: 5.31, 5.92, t(96) = 10.56, p < .001) and Republican participants (MRating = 5.69, CI95: 5.39, 5.99, t(102) = 11.32, p < .001).

Charity Diversity. Finally, we assessed whether stimuli diversity within-papers would be related to liberal skew. Papers with more stimuli arguably sample from a pool of cause areas that are disproportionately liberal to begin with. To that end, we counted the number of stimuli in each paper in our dataset and tested whether stimuli count predicted each papers’ average stimuli political valence using a simple univariate linear regression. We observed no significant effect of stimuli count on average political valence (β = -0.01, CI95: -0.03, 0.01, t(97) = -1.28, p = 0.203), such that papers using more stimuli did not exhibit a higher liberal skew than papers with fewer stimuli.

Discussion

In this study, H1 and H3 were supported, while H4 was not supported. We observed a significant liberal skew in the cause areas and stimuli investigated by prosocial consumer behavior researchers, thus supporting H1. Consistent with H3, we observed zero cases of religious cause areas, which our participants rated as highly conservative, despite religious cause areas accounting for the single largest share of donations in the United States (Giving USA 2023). Finally, our analysis of stimuli diversity as an explanation of liberal skew was unsupported, such that papers with more stimuli were not associated with increased liberal skew (H4). We further explore potential mechanisms for our observed stimuli skew in study 2, which measures the preferences and beliefs of contemporary prosocial behavior researchers.

Study 2

The primary purpose of study 2 was to assess if the political preferences of researchers is predictive of the political leaning of stimuli in prosocial consumer behavior research, particularly a preference for more liberal (vs. conservative) causes. In addition, we wanted to assess how these preferences relate to a willingness to discriminate against researchers and cause areas of an opposite political persuasion (H2). Our design draws in part from Inbar and Lammers (2012), who conducted a similar survey of personality and social psychology researchers politics, but was not specific to prosocial consumer research.

Method

We recruited 302 participants via email, using a mailing list of researchers listed as co-authors in all papers included in our study 1 review and a list of attendees at a conference primarily attended by prosocial consumer behavior researchers. Our email recruitment method yielded an overall response rate of 32.12%, representing 97 participants (Gender: 54.6% women, 44.3% men, 1.03% non-binary), which exceeds the response rates of 26.2% and 30.9% achieved in similar surveys (Inbar and Lammers 2012; Klein and Stern 2005). Our final sample represented a diversity of ages and degrees of seniority, albeit skewed towards tenured and tenure-track professors (see Table 1). All stimuli and measures used can be found in web appendix B.

We first asked all participants to name a charity that they would like to enter into a draw to receive a $400 donation from the research team. These responses enabled a real-life measure of participants’ preferences for charities of specific political persuasions. Ultimately, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) was the recipient of the $400 donation.

Next, following Inbar and Lammers (2012), we asked participants to rate their political beliefs on social issues, economic policy, foreign policy, and overall political identification on a 1 (“Very conservative”) to 7 (“Very liberal”) scales. These measures were counterbalanced to appear at either the beginning or end of the survey to guard against concerns over priming political ideology. We expected that participants would rate themselves as generally liberal, especially with respect to social issues.

We next asked participants to identify whether a set of cause area features were relevant to their selection of stimuli. Specifically, participants were asked to identify if 1) personal support for a cause, 2) societal support for a cause, 3) participants’ support for a cause, 4) personal connection to a cause, or 5) use of a cause in prior research was relevant to their stimuli selection. We expected that researchers would identify personal support for and connection to a cause area as relevant criteria in stimuli selection, and at comparable rates to other selection strategies like selecting stimuli used in prior research or expectations of societal support.

Finally, we asked participants to rate their agreement with a series of statements related to their own willingness to discriminate against ideologically incongruent researchers and cause areas, as well as their perceptions of their colleagues’ willingness to do so (1—7; 1 = “Strongly disagree”, 7 = “Strongly agree”). Specifically, we asked participants if they would 1) be willing to “[write] a paper exploring how to motivate donations to a charity [they] oppose” (reverse-coded), 2) be “biased against (e.g., would evaluate more harshly) a paper exploring how to motivate donations to a charity [they] oppose in the peer review process,” and 3) be “biased against (e.g., would evaluate more harshly) job market candidates who wrote a paper exploring how to motivate donations to a charity [they] oppose.”

We measure both self-reported willingness to discriminate and perceived willingness to discriminate by other prosocial behavior researchers to mitigate concerns over social desirability bias in self-reports (Fisher 1993). We expected that a substantial fraction of researchers would identify as being likely to discriminate, but that perceptions of colleagues’ willingness to do so would be higher.

Results

Real-world charity selection. We coded participants’ choice of charity (N=80, excluding non-respondents) according to the same criteria used in study 1. We found that participants primarily nominated left-wing (55%) and neutral charities (42.5%) for the $400 draw, while two participants nominated a conservative charity (2.5%; both religious organizations). These rates roughly align with the political distribution of stimuli observed in study 1.

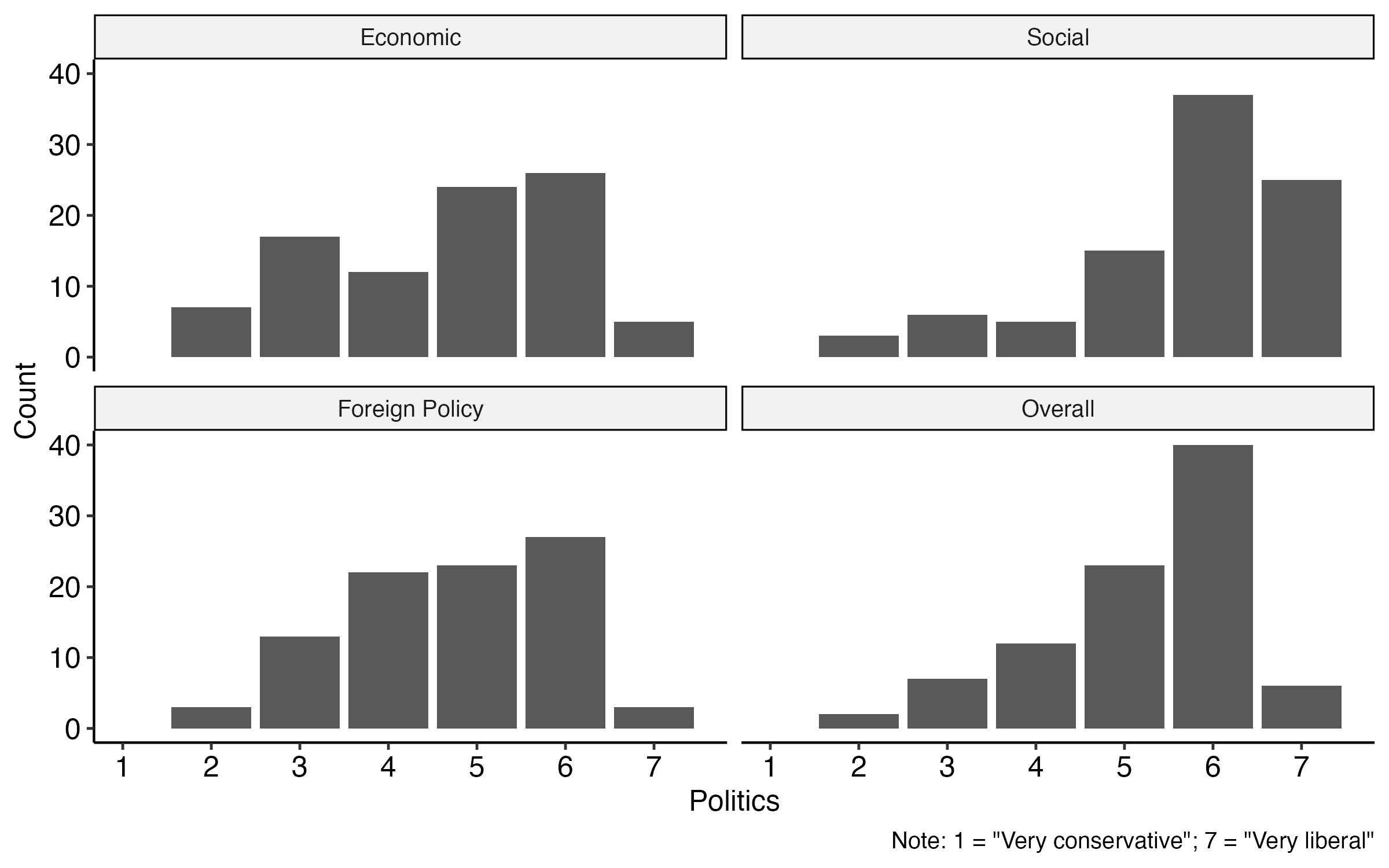

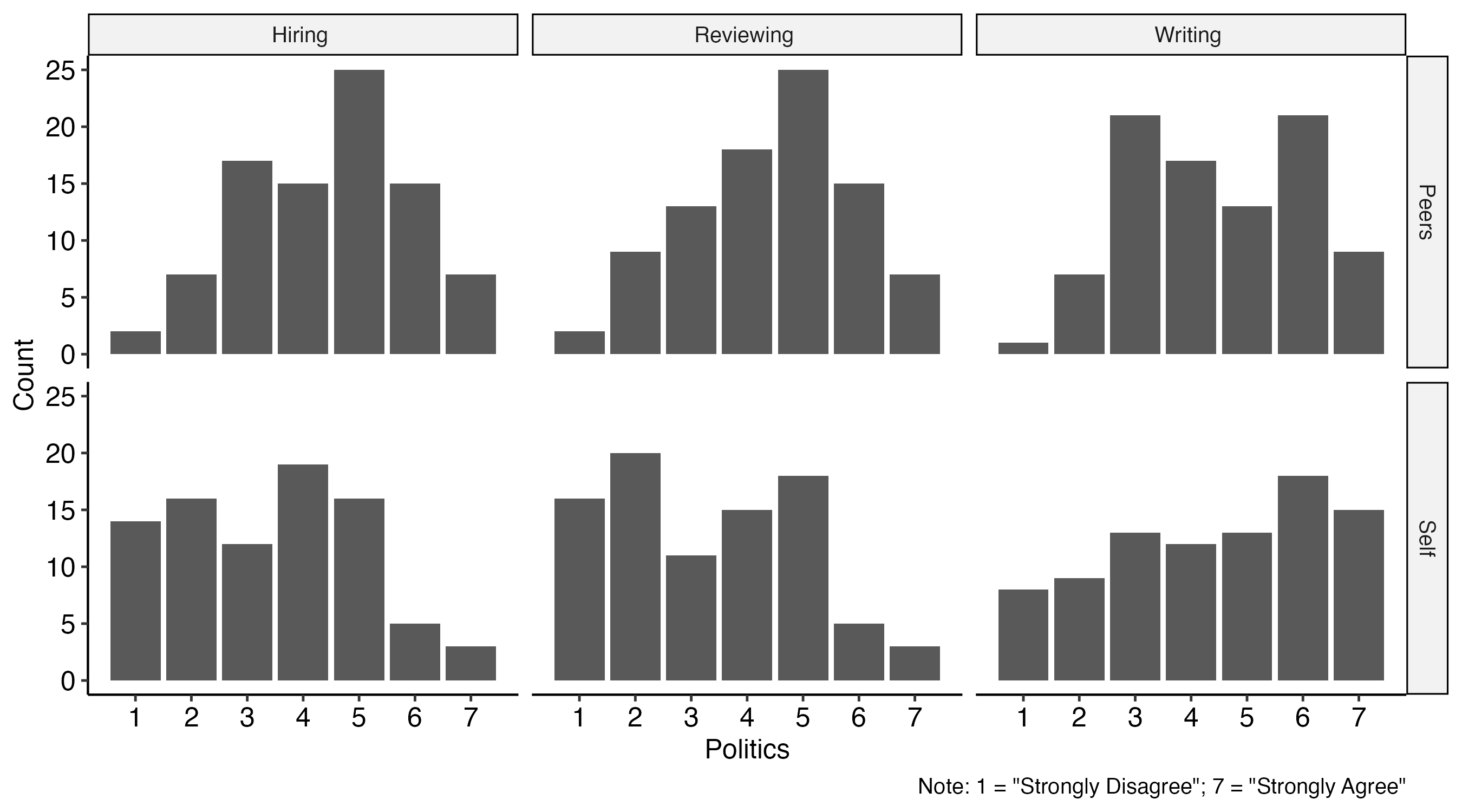

Political beliefs. Consistent with our theorizing, and with the findings of previous surveys (e.g., Inbar and Lammers 2012), participants generally rated themselves as above the scale midpoint of 4 (e.g., liberal) with respect to economic policy (MRating = 4.66, CI95: 4.37, 4.95, t(90) = 4.47, p < .001), social issues (MRating = 5.67, CI95: 5.4, 5.94, t(90) = 12.26, p < .001), foreign policy beliefs (MRating = 4.74, CI95: 4.48, 4.99, t(90) = 5.76, p < .001), and overall liberal identification (MRating = 5.22, CI95: 4.98, 5.46, t(89) = 10.09, p < .001). These results are consistent with past surveys of academics’ politics. Notably, participants’ self-reported economic policy beliefs, while significantly above the scale midpoint, were noticeably less left-wing than participants’ self-reported beliefs with respect to social issues (MRating = -1.01, CI95: -1.3, -0.72, t(90) = -6.84, p < .001) or foreign policy (MRating = -0.93, CI95: -1.19, -0.68, t(90) = -7.26, p < .001). This result is consistent with previous findings that being more economically informed (as the many business professors comprising our sample no doubt are) makes individuals relatively more likely to endorse some conservative economic policies (e.g., Caplan 2008, chap. 3). Overall, 76.67% of participants self-identified as at least somewhat liberal, and 10.00% as at least somewhat conservative. We visualize the distribution of participant responses in Figure 5.

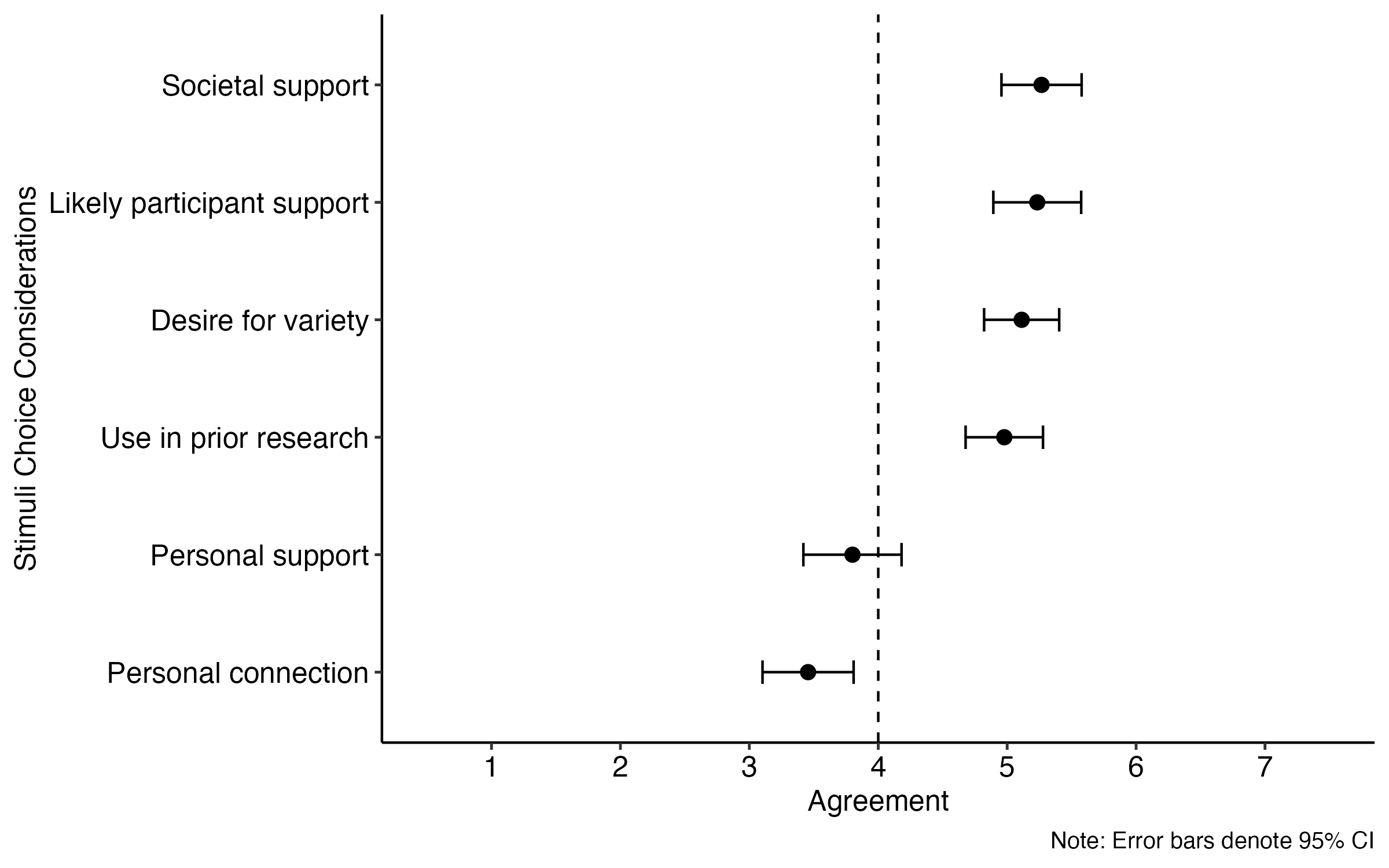

Stimuli selection. Most considerations for stimuli selection were broadly agreed upon by participants to be relevant. Participants’ support for a cause (MRating = 5.23, CI95: 4.89, 5.58, t(89) = 7.09, p < .001), societal support for a cause (MRating = 5.27, CI95: 4.95, 5.58, t(89) = 7.98, p < .001), desire for variety (MRating = 5.11, CI95: 4.82, 5.41, t(88) = 7.49, p < .001), and use in prior research (MRating = 4.98, CI95: 4.67, 5.28, t(89) = 6.38, p < .001) were all rated significantly above the scale midpoint. Contrary to our theorizing, participants were generally ambivalent with respect to whether personal support for a cause factored into their stimuli selection decisions (MRating = 3.8, CI95: 3.41, 4.19, t(89) = -1.03, p = 0.306) and generally disagreed that personal connections to causes factored into their stimuli selection decisions (MRating = 4.66, CI95: 4.37, 4.95, t(90) = 4.47, p < .001; see Figure 6). Given the overrepresentation of liberal causes (and underrepresentation of conservative causes) we observe in the literature, these results suggest that researchers are either mistaken about the degree to which personal connections factor into stimuli selection, or that researchers’ dislike of ideologically incongruent stimuli drives the disparity we observe.

Bias against ideologically incongruent charities. We show the full distribution for each of our bias measures in Figure 7. We also report the mean, standard deviation, and proportion of responses above the scale midpoint in Table 2. A substantial proportion of participants rated that they, at minimum, were neutral on whether they would be unwilling to write papers exploring donations to ideologically incongruent charities (65.91%), that they would be biased against papers exploring ideologically incongruent charities in the review process (46.59%), and that they would be biased against job market candidates who wrote such papers (50.59%). These sentiments were also seen in participants’ open-ended remarks (see Table 3 for sample excerpts). These results are much more extreme than those observed by Inbar and Lammers (2012), who found rates of 18.6% and 37.5% for agreement about bias in paper review and hiring decisions, respectively, whereas we observe rates of 47% and 51%.

Participants generally gave self-reported bias estimates that were significantly below the scale midpoint for both bias against ideologically congruent papers in the review process (MRating = 3.3, CI95: 2.93, 3.66, t(87) = -3.85, p < .001), and job market candidates who write such papers (MRating = 3.4, CI95: 3.04, 3.76, t(84) = -3.31, p = 0.001) but significantly above the midpoint with respect to willingness to write about ideologically incongruent charities (MRating = 4.44, CI95: 4.03, 4.85, t(87) = 2.16, p = 0.034). As anticipated, participants perceived their peers as being more willing (relative to themselves) to be biased against ideologically incongruent research in the review process (MRating = 4.44, CI95: 4.12, 4.75, t(88) = 2.76, p = 0.007; Δ = -1.14, CI95: -1.62, -0.66, t(171) = -4.71, p < .001) and hiring process (MRating = 4.44, CI95: 4.13, 4.76, t(87) = 2.79, p = 0.007; Δ = -1.04, CI95: -1.52, -0.57, t(167) = -4.33, p < .001), though peers were rated as being similarly (not) open to writing papers about ideologically incongruent charities (MRating = 4.49, CI95: 4.17, 4.82, t(88) = 2.99, p = 0.004; Δ = -0.05, CI95: -0.57, 0.47, t(167) = -0.19, p = 0.846).

Discussion

These results offer preliminary evidence for H2b, showing that a general bias against ideologically incongruent research may explain, in part, the preference for liberal stimuli that we observe in study 1. Evidence for H2a—that this bias is caused by personal support among researchers—is mixed, as researchers generally rated themselves as ambivalent or generally disagreeing with the suggestion that their stimuli selection decisions are attributable to personal connections or support for cause areas. We, therefore, view H2b as a stronger, and perhaps more plausible, explanation of the bias we observe in the literature, though there is more to be said about how to interpret participants’ responses to the self and peer-reported bias questions.

The gap between participants’ self-reported biases and their reports of peers’ biases against ideologically incongruent charities could be interpreted in two ways. First, one could consider peer ratings more reliable insofar as they function as indirect questioning about a behavior with substantial risk of social desirability bias (Fisher 1993). This interpretation would suggest that the researchers in our sample were somewhat more biased than they were aware of or willing to indicate, which some participants noted as a possibility in their open-ended responses. Alternatively, one could view the gap between self-ratings and peer ratings as indicating that researchers may overperceive the degree to which exploring ideologically incongruent charities would be poorly received by their peers. We take no specific stance as to which interpretation is correct but note that either suggests that scholars working on ideologically incongruent charities face substantial risk of harsher evaluations from their peers, both in the review process and on the job market, which may explain the imbalance in stimuli used in the literature that we observe in study 1.

Not only do the results of this survey illuminate plausible mechanisms for the liberal skew we observe in the literature, but they also guide how we think about solutions to the problem. For example, several participants gave thoughtful open-ended responses about the moral difficulties involved in motivating donations to ideologically incongruent charities (e.g., asking a gun control advocate how to motivate donations to the NRA). These concerns are legitimate and make asking researchers to simply do more research on ideologically incongruent charities seem like both an unfair demand and an infeasible plan. In our remaining studies, we investigate two ways that researchers could better address the risk of political bias in stimuli and the accompanying distortion in findings: 1) account for the political valence of charities, and 2) measure participants’ political beliefs as a covariate.

Study 3

The purpose of study 3 was to identify how the political valence of prosocial stimuli can function as a hidden moderator for individual differences linked to political ideology (H5). For this, we replicate a recent study from Milne, Kristofferson and Goode (2024) and demonstrate that the estimated effect of politically correlated individual differences on donation behavior can change depending on whether the political valence of stimuli is taken into account.

In study 3, we estimate the effects of both Left-Wing Authoritarianism (LWA) and Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) on donation. In general, authoritarianism is a personality type that is associated with antisocial values and behaviors submission to authority figures, aggression towards perceived enemies, and a degree of dogmatism or cognitive rigidity with respect to ideological beliefs (Altemeyer 1996; Costello et al. 2022). Additionally, authoritarianism has historically been regarded as negatively correlated with prosocial behavior (Costello et al. 2022). However, this seemingly negative relationship between authoritarianism and prosocial behavior may actually be due to the use of a limited set of charitable stimuli in past research. Indeed, Milne et al. (2024) found that when authoritarians (left or right) are presented with donation options that come with retributive benefits (offer both charitable benefits and invoke punishment of intentional wrongdoers who violate their respective value systems), they are more likely to donate. The punishment benefit offered in the stimuli used by Milne et al. (2024) was congruent with the value system and proclivities of authoritarians and, hence, increased their donations. These findings indirectly support our contention that congruence between individual differences and the political valence of the stimuli matters. Thus, we use the same retributive donation context and leverage this novel perspective of authoritarian personalities and donation behavior to test H5.

Specifically, we propose that estimates of the effect of authoritarianism on donation will be muted when authoritarianism is assessed against stimuli that contains both ideologically congruent and ideologically incongruent donation options, as authoritarians will naturally prefer congruent options but not prefer incongruent options. Moreover, we propose that including the political valence of stimuli as a moderator of authoritarianisms’ effect will result in a more realistic and robust test of its effect on donation.

Method

Prolific Academic participants (N = 802, ages 18-94, MAge = 42.91, 50% female) completed this study in exchange for financial payment and were randomly assigned to conditions in a 2-factor (norm violation: liberal vs. conservative) pre-registered between-participants design (https://aspredicted.org/316_2BR). Per our pre-registration, we recruited two independent samples of left-wing and right-wing partisans in two simultaneous waves on Prolific Academic. Our first wave of recruitment consisted of 401 self-identified Democrats. Our second wave consisted of 401 self-identified Republicans.

All participants first completed one of our two authoritarianism measures: Democrats completed the LWA scale (1 = “strongly disagree, 7 = “strongly agree”; e.g., “Getting rid of inequality is more important than protecting the so-called ‘right’ to free speech.”), whereas Republicans completed the RWA scale (1 = “strongly disagree, 7 = “strongly agree”; e.g., “Our country will be destroyed someday if we do not smash the perversions eating away at our moral fiber and traditional beliefs”). Participants were then randomized to view one of two stories that either violated liberal or conservative norms. Participants in the left-wing norm violation condition read a story of a non-Black professor using the N-word in front of students, which many liberal individuals care about; participants in the conservative norm violation condition read a story of a professor who exposed students to “transgender ideology”, which many conservative individuals care about. Two separate norm violation conditions and corresponding charitable stimuli were needed because left-wing and right-wing authoritarians have different (often opposing) sets of values, such that a scenario perceived by left-wing authoritarians as a norm violation may not be seen as a norm violation by right-wing authoritarians and vice versa. Participants then rated willingness to donate to a charity (1 = “definitely not”, 7 = “definitely yes”) that promised to 1) help victims of the professor, and 2) send letters to the professor’s school calling for their dismissal for every donation received. All stimuli and measures used can be found in web appendix B.

Results

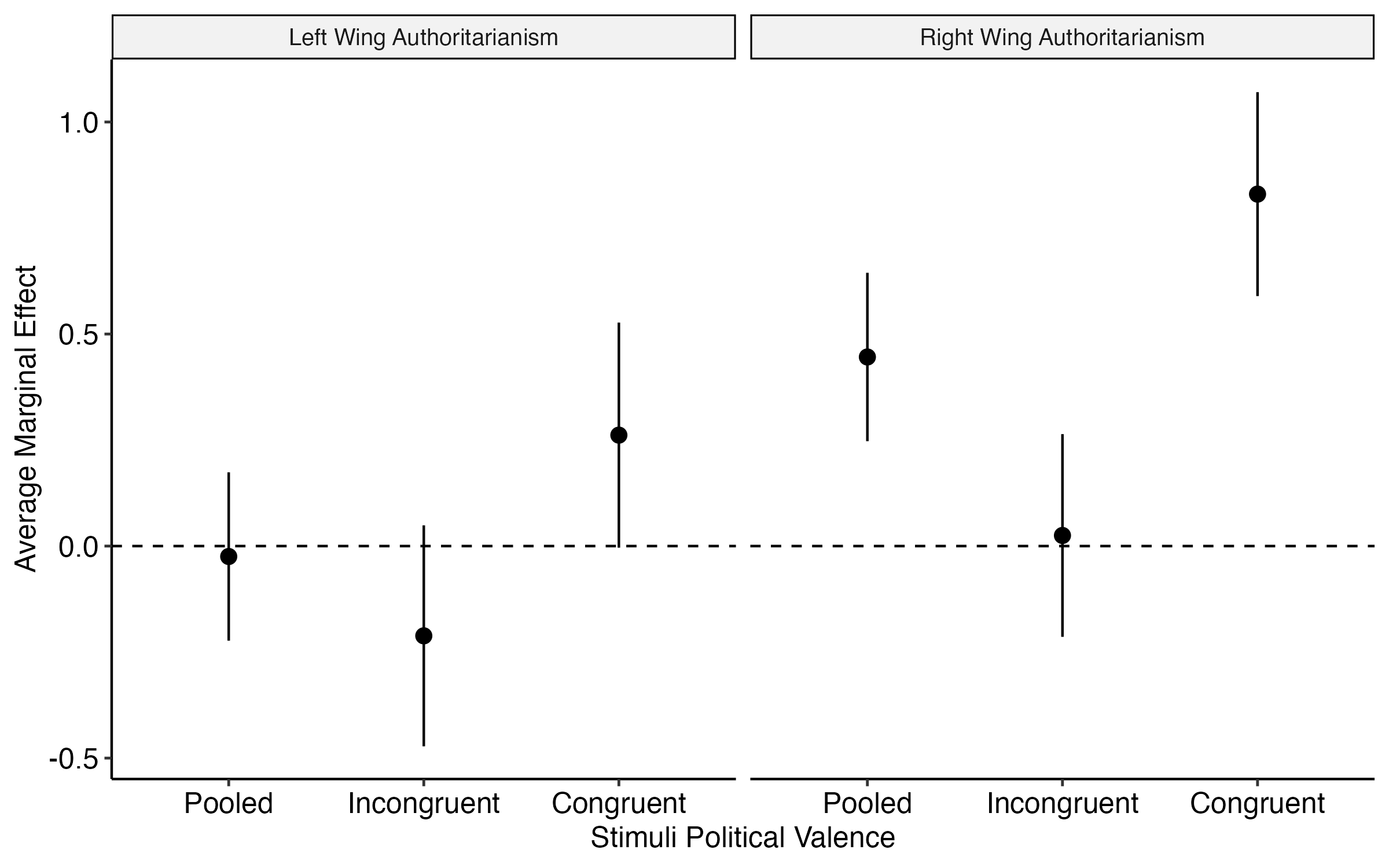

Per our pre-registration, we conducted analyses of the effects of both LWA and RWA for each sample on donation intentions. These analyses tested the effect of authoritarianism (left- or right-wing) on donation using either 1) a pooled sample of our stimuli conditions (e.g., left-wing or right-wing norm violations), or 2) using the political valence of stimuli as a moderator of each sample’s respective authoritarianism scale, which enables a test of H5. For simplicity, we refer to stimuli conditions as being either congruent (e.g., for the left-wing sample, the left-wing norm violation and corresponding left-wing charity) or incongruent (e.g., for the right-wing sample, the right-wing norm violation and corresponding right-wing charity).

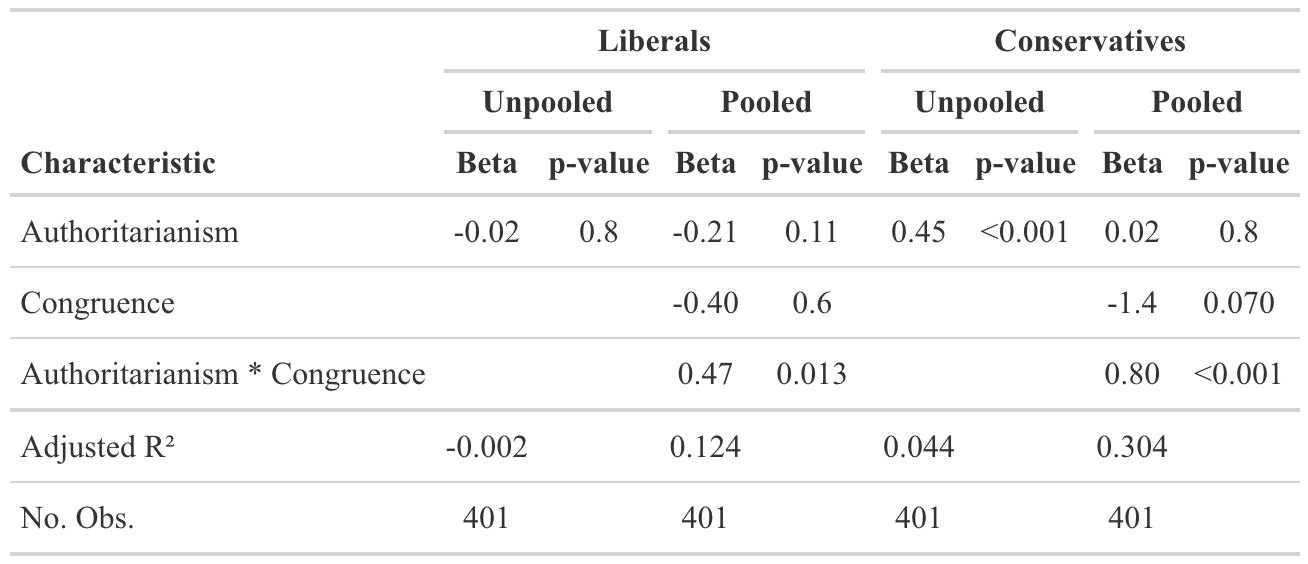

Consistent with our theorizing, the estimated effect of authoritarianism was muted when ideologically congruent and ideologically incongruent stimuli were pooled. For left-wing participants, there was no effect of LWA on donation ( = -0.02, 95% CI95: -0.22, 0.17 t(399) = -.24, p = .808); for right-wing participants, there was a positive effect of RWA on donation ( = 0.45, CI95: 0.25, 0.65, t(399) = 4.40, p < .001). These small positive effects are likely attributable to floor effects: participants across all levels of RWA or LWA did not significantly vary in their donation intentions when presented with ideologically incongruent stimuli, because even individuals low in authoritarianism tended not to support ideologically incongruent cause areas.

In our secondary models using the political congruence of stimuli as a moderator, we observed positive effects of LWA and RWA on donation when the charitable stimuli was ideologically congruent with the values of the respective authoritarian personality (LWA: = 0.47, CI95: 0.10, 0.85, t(397) = 2.49, p = .013; RWA: = .80, CI95: 0.46, 1.15, t(397) = 4.65, p < .001). Only null effects were observed when stimuli were incongruent (LWA: = -.21, CI95: -.47, .05, t(397) = -1.59, p = 0.11; RWA: = .02, CI95: -0.21, 0.26, t(397) = .20, p = .838). Figure 8 depicts the marginal effect estimates of LWA and RWA for the pooled analysis, and both conditions (congruent and incongruent) of the unpooled analysis. Importantly, we only observe positive marginal effects of either measure of authoritarianism when participants were presented with congruent stimuli.

Finally, for both Republicans and Democrats, the model including the political valence of stimuli as a predictor drastically outperformed the pooled model with respect to explaining variance in participants’ choice of charity (LWA: F(2, 397) = 200.28, p < .001; RWA: F(2, 397) = 480.85, p < .001), with the pooled analyses explaining between 0% and 4.4% of variance, and the unpooled analyses explaining between 13.1% and 30.4% of variance (see table 4).

Discussion

These results suggest that pooling the effects of authoritarianism across ideologically congruent and ideologically incongruent stimuli will produce muted effect sizes (H5). In the case of authoritarianism (left or right), it is unlikely that authoritarians of either political persuasion would consider donating to ideologically incongruent charities, and thus using politically incongruent stimuli in research would not be reflective of real-world consumer behavior.

We, therefore, recommend that researchers estimating the effects of politically correlated individual differences on donation should 1) use either neutral or balanced sets of stimuli, or 2) explicitly consider and test for effects of congruence between the individual differences in question and the political valence of their chosen stimuli as we did in this study.

Study 4a

Whereas study 3 investigated how failing to account for the political nature of stimuli can distort estimates of effects, we contend in study 4a that not accounting for the political beliefs of participants may also distort estimates of effects by erroneously inflating or deflating the relationship between certain individual differences (i.e., those associated with political beliefs) and donations to political causes (H5). study 4a provides further evidence for the downsides of politically homogenous stimuli when political beliefs are not measured: overestimation of the effect of an individual difference on donation behavior.

We specifically chose to focus on empathy as an individual difference that might plausibly be confounded by liberal identification. Empathy tends to be correlated with liberal political beliefs (Hasson et al. 2018), so the effect of empathy on donation to liberal charities could be partially attributable to participants’ correlated political beliefs. We, therefore, test whether the effect of empathy on donation is attenuated when political beliefs are included as a covariate, and whether this attenuation only occurs for liberal charities or for neutral charities as well. We expected that the effect of empathy on donation to both cause areas would be positive, but that the effect of empathy on donation would be attenuated for the liberal cause area but not for the neutral cause area. Such a finding would support our contention that using political stimuli can risk generating confounded estimates of the effects of certain individual differences on donation when political beliefs are not measure.

Method

Undergraduate participants (N = 606, MAge = 19.22, 36.6% female) completed this study for course credit and were randomly assigned to conditions in a 2-factor (cause area: left-wing vs. neutral) between-participants design. In a lab pre-survey conducted months prior to the focal study, participants completed a 7-point scale representing their political beliefs (1 = “strongly left-wing”, 7 = “strongly right wing”). Participants expressed a range of political beliefs, centered around the midpoint of the scale (MPolitics = 4.08, SDPolitics = 1.22).

At the onset of the study, all participants completed a 5-point, single-item trait empathy scale [Konrath, Meier and Bushman (2018); “I am an empathetic person”; 1 = “not very true of me”, 7 = “very true of me”]. Participants were then shown one of two cause areas and asked to rate their likelihood of donation (1—7; 1 = “extremely unlikely”, 7 = “extremely likely”). Specifically, participants were shown a cause area that was rated in study 1 as very liberal (immigrant absorption; N = 304) or neutral (cancer research; N = 302). All stimuli and measures used can be found in web appendix B.

Results

We first observed a negative correlation between empathy and political beliefs, such that conservative participants self-reported being less empathetic than liberal participants (r = -.16). This result suggests that the estimated relationship between empathy and donation to a political cause area could plausibly be confounded by political beliefs.

We then fit four complementary linear regression models, all of which estimated the effect of trait-empathy on donation, split by whether or not participants’ political beliefs were included as a potential confounder, and whether the cause area in question was liberal or neutral (see table 5). Across all models, we observed significant effects of empathy on donation, such that more empathetic participants reported higher likelihood of donation.

We further observed a significant effect of political beliefs on donation for the liberal cause area, such that more liberal participants reported being more likely to donate to assist with immigrant absorption ( = -.23, CI95: -.39, -.07, t(301) = 5.27, p < .001). No such effect was observed for the neutral charity ( = -.02, CI95: -.15, .12, t(299) = -0.25, p = .802).

Central to our theorizing, there was a notable attenuation of the effect of empathy on donation for the liberal cause area after including political beliefs as a covariate. Specifically, the effect of empathy dropped from 0.43 (CI95: .22, .65, t(302) = 4.00, p < .001) to 0.38 (CI95: .16, .59, t(301) = 3.46, p < .001) after controlling for political beliefs. This represents an attenuation of 12.9%, which exceeds the commonly used 10% change-in-parameter threshold for identifying confounds used in prior research (Grayson 1987; Hernán et al. 2002).3 No such attenuation was observed for the non-partisan cause area, which had nearly identical effects of empathy on donation in the univariate model ( = .49, CI95: .31, .67, t(300) = 5.27, p < .001) compared to the bivariate model ( = .49, CI95: .30, .67, t(299) = 5.18, p < .001). The bivariate model was a better predictor of donation than the univariate model for the liberal stimuli (F(1, 301) = 7.80, p = .005), but there was no difference between models for the non-partisan stimuli (F(1, 299) = .06, p = .802).

Discussion

These results suggest that the unacknowledged political beliefs of participants can erroneously inflate estimates of some individual differences on donation, specifically in cases where stimuli are politically congruent with participants’ political beliefs (H5). While this study primarily focuses on how an unacknowledged confound could erroneously inflate the estimated effect of a politically correlated individual difference, there is a symmetrical risk of attenuation. For example, with individual differences that tend to be correlated with conservative political beliefs, the estimated effects of such individual differences on donation to the liberal stimuli used in the literature may in fact be erroneously deflated.

This study is limited, however, in that we only demonstrate the confounding potential of participants’ political beliefs across a single pair of liberal and non-partisan cause areas. However, Simonsohn, Montealegre and Evangelidis (2024) note that a diverse range of stimuli are often employed to manipulate highly abstract latent constructs, and that individual stimuli can themselves have unique internal confounders that make studies based on single stimuli less reliable. Researchers may therefore simply settle on stimuli that produce the results they expect (and, as we contend, align with their political beliefs), regardless of whether the particular stimuli chosen produces the hypothesized effect because of the latent variable of interest, rather than some other confound. Thus, in study 4b we conduct a similar experimental procedure as in study 4a but include a diverse range of liberal and non-partisan stimuli to demonstrate consistency in our results.

Study 4b

The purpose of study 4b is to replicate, across a diverse range of stimuli, the results of study 4a. We again selected empathy as an individual difference that is both correlated with liberal political beliefs and has been repeatedly shown to be related to prosocial behavior in prior work (Eisenberg and Miller 1987). We expect to observe similar attenuation of empathy’s relationship to donation when political beliefs are added as a covariate across all of the liberal cause areas but no attenuation for neutral cause areas.

Method

Prolific Academic participants (N = 600, MAge= 41.64, 50% female) completed this study for financial compensation. We specifically recruited a balanced sample of 50% (N=300) self-identified Democratic voters and 50% (N=300) self-identified Republican voters to ensure a diversity of political beliefs in our sample. Twenty-five participants were excluded for failing a basic attention check, resulting in a final sample of 575. Our data collection, exclusion, and analysis plans were pre-registered at https://aspredicted.org/QPR_T1G.

Participants first completed the same trait-empathy measure as in study 4a and then rated their political beliefs on a 1—7 scale (1 = “very liberal”, 7 = “very conservative”). Participants were shown, in random order, a set of eight stimuli which represented four liberal cause areas (immigration, indigenous rights, COVID-19, environmental conservation) and four neutral cause areas (cancer research, helping natural disaster victims, donating blood, supporting sick children) that were identified in study 1. Participants were asked to rate their likelihood of donating to each cause area on a 1—7 scale (1 = “extremely unlikely”, 7 = “extremely likely”). All stimuli and measures used can be found in web appendix B.

Results

We analyzed our data in a similar fashion to study 4a. For each cause area, we estimated a univariate model of the relationship between empathy and donation likelihood. We then estimated a bivariate model of the same relationship but included political beliefs as a covariate. For each cause area, we made two primary comparisons. First, we calculated the extent to which empathy’s estimated relationship with donation likelihood was reduced upon moving from a univariate to a bivariate model (see figure 9). Second, we compared model performance between the univariate and bivariate models for each stimulus (see figure 10).

Across all liberal cause areas, we observed reductions in the estimated relationship between empathy and donation likelihood between our univariate and bivariate models, though we did not observe a reduction greater than 10% for two cause areas. We observed no such reductions for the non-partisan cause areas. We also observed substantial gains in the proportion of variance explained between models but only for liberal causes.

Discussion

Overall, these results replicate and support the findings of study 4a. For individual differences like trait-empathy, which are related to both political beliefs and donation, unmeasured political beliefs of participants pose a higher risk of confounding when stimuli are also liberal. While there was some heterogeneity in which liberal cause areas saw substantial confounding from political beliefs, the cause areas that did see substantial changes in effect estimates are, nevertheless, popular domains of inquiry for prosocial consumer behavior research. Environmental conservation alone was associated with a 10% reduction in coefficient estimates for the effect of empathy, and this specific cause area represents approximately 10.5% of all stimuli used in contemporary prosocial consumer behavior research (based on our literature review from study 1).

General Discussion

In 1942, the sociologist Robert Merton proposed a set of four norms that have since been called the “Mertonian Norms” of science (Frisby 2023; Merton 1942). In short, good science ought to adhere to the principles of 1) Universalism, such that scientific knowledge does not depend on who is doing the science, 2) Disinterestedness, such that science is pursued for common benefit, rather than to advance one’s particular ideological or personal aims, 3) Communality, such that results are shared freely with others for replication and critique, and 4) Organized Skepticism, such that no conclusions are treated as sacred and are always subject to challenge. No individual scientist could possibly always meet such criteria, yet as a collective it is important that these norms are generally observed to protect against systematic bias.

The results of our research suggest that contrary to the Mertonian Norms of universalism and disinterestedness, there exists a systematic bias in the prosocial consumer behavior literature. We contribute to the prosocial consumer behavior literature by showing that that liberal cause areas are overrepresented and conservative cause areas are greatly underrepresented in the stimuli used by prosocial consumer behavior researchers (study 1). Moreover, we demonstrate that prosocial consumer behavior researchers are overwhelmingly liberal in several domains (e.g., economic policy, foreign policy, social issues), as well as in overall political identification (study 2). Researchers expressed a high degree of willingness to be biased against research about ideologically incongruent charities and against those who conduct such research, as well as a correspondingly low willingness to conduct such research themselves (and expected their colleagues to be even more biased). Finally, we spotlight potential consequences of this bias. On a theoretical level, we argue that the omission of conservative cause areas has resulted in a neglect of the unique features of conservative charitable giving in contemporary theorizing about the motivations, emotions, and behaviors involved in prosocial consumer behavior. On a practical level, we provide evidence that the unexamined political valence of stimuli can function as a hidden moderator of effects that prosocial behavior researchers are interested in (study 3), and unmeasured political beliefs of participants may present a similar risk, insofar, as they confound estimates of the effect of individual differences on prosocial behavior towards politicized stimuli (studies 4a and 4b).

In summary, we contribute to the prosocial consumer behavior literature by documenting a pervasive bias against conservative causes in the overall literature, the review process, and the academic job market, and demonstrate that this bias is consequential. It can distort research findings and leave important gaps in our collective theoretical understanding of prosocial consumer behavior. We next discuss additional practical implications of this research.

Practical Implications

While we identify a substantial bias against conservative cause areas in the literature, striving for an equal balance of liberal and conservative cause areas in the literature is not necessarily a desirable target. Perhaps some cause areas, such as environmental conservation, are both more reflective of liberal values and are also more important and urgent areas of research than some conservative cause areas. One might argue that an overrepresentation of liberal cause areas (and underrepresentation of conservative cause areas) is, therefore, preferable as it allows researchers to prioritize those cause areas that they perceive to be more impactful.

However, if one takes the view that the purpose of prosocial consumer behavior research is not only to create a better world, but also to contribute to a scientific understanding of the phenomenon of prosocial consumer behavior, a more nuanced picture emerges. This last consideration is key; a bias in topic area could be consistent with a focus on impact, but the wholesale omission of conservative cause areas that we identify means that our theoretical frameworks of prosocial behavior remain incomplete, as they do not adequately integrate the unique psychological, moral, and political features of such donations. Additionally, prior research has demonstrated that when scientific institutions, such as academic journals, are perceived as politically motivated, trust in these institutions is undermined among consumers with incongruent political beliefs (Zhang 2023). A loss in legitimacy resulting from political skew in our research would be detrimental to our aims of leveraging research to promote a better world (Chandy et al. 2021). We, therefore, have several recommendations for researchers, reviewers, editors, and other scholars working in the prosocial consumer behavior domain.

Research conservative cause areas. The results of our literature review in study 1 suggest that there is a systematic omission of conservative cause areas in our field—especially donations to religious institutions, despite such donations being the single largest source of donations in the United States (Giving USA 2023). Additionally, participants’ survey responses in study 2 suggest a low willingness to conduct research on ideologically incongruent causes.

Given the differences in moral values and psychological tendencies between liberals and conservatives (e.g., Graham et al. 2009; Winterich et al. 2012), we expect that there are many opportunities for research exploring the unique features of conservative donation to make a contribution to the prosocial consumer behavior literature. For example, Goenka and Osselaer (2019) provide compelling evidence that the traditionally-left-wing moral foundations of care and fairness can increase donations when paired with congruent emotions of compassion and gratitude. However, the remaining three moral foundations proposed by Graham et al. (2009) remain unexplored and open to new investigation—which emotions pair best with the moral foundations of loyalty, authority, and purity? Future research could investigate how patriotism, for instance, pairs well with charities that emphasize loyalty to one’s country, such as donations to the military. Thus, researchers might fruitfully explore such topics, as they have the potential to contribute to current theory about the nature and causes of prosocial consumer behavior.

Challenge biases. The results of our survey of prosocial consumer researchers (study 2) suggest that there are considerable barriers to conducting research on conservative cause areas. In particular, we identify a high degree of bias against research about ideologically incongruent cause areas and the researchers thereof. We have two principal recommendations to address this issue, targeted to researchers as well as to journal editors and review teams.

Researchers examining prosocial consumer behavior should critically evaluate their projects and question the degree to which their chosen stimuli are politically valenced. Researchers should then explicitly discuss how the political nature of their stimuli may influence their results. For example, researchers should carefully consider why using primarily liberal stimuli is appropriate, such as in cases where the participant pool is overwhelmingly politically liberal or when the research is about a particular cause area that is already politicized. Moreover, the political nature of selected stimuli should factor into researchers’ discussions about the generalizability of their results. For example, research that explores novel causes of donations only in the context of liberal causes may only apply to liberal consumers, not consumers in general. By thoughtfully considering how bias in stimuli selection impacts the generalizability of their research, we believe that researchers will come to understand the value of considering the implications of diversity of stimuli in their own research, as well as the research of others.

Journal editors and reviewers of prosocial consumer behavior papers would do well to consider researching conservative cause areas and conservative populations as a point of differentiation for manuscripts. Furthermore, editors and reviewers could encourage authors, when appropriate, to demonstrate convergent evidence for their focal effects using a range of charitable stimuli that activates a diversity of political and moral beliefs. These recommendations would both reduce barriers for research, specifically related to conservative cause areas, as well as normalize the use of conservative cause areas to test the generalizability of research findings.

Importantly, our recommendations should not be done with the goal of simply achieving parity in representation between liberal and conservative cause areas for its own sake. Rather, implementing our recommendations may empower prosocial consumer behavior researchers to conduct research on conservative cause areas when relevant to their specific research questions, without fear that such research will be subject to harsher evaluations in the review or hiring process. In other words, research on conservative cause areas should not be artificially encouraged past the point at which it can contribute to our understanding of prosocial consumer behavior. Our aim is to eliminate barriers to research on the unique features of conservatives’ donation behaviors, not to promote such research at the expense of other worthwhile pursuits.

Account for the political nature of stimuli. Our work also suggests that researchers can take steps to mitigate the distortive impact of bias in stimuli selection on study results. In study 3, we demonstrate that the unmeasured political valence of stimuli can artificially accentuate or attenuate the estimated relationship between some individual differences and donation. When possible, we recommend that researchers use neutral stimuli to mitigate this risk.

However, using neutral stimuli is not always appropriate. Some cause areas—such as environmental conservation or free speech—are tightly linked to partisan disputes and thus come with increased risks of confounded analyses of the relationship between some individual differences and donation. We recommend that, when using political stimuli, researchers measure participants’ political beliefs and include these are covariates in their statistical models of donation behavior to account for confounding risk.

Future Research Directions

While our research identifies and evaluates several possible mechanisms for stimuli skew in the prosocial consumer behavior literature, this phenomenon is likely multiply determined. Future research may further explore additional mechanisms that could plausibly generate a bias in stimuli selection. For example, the student populations that researchers tend to sample from also exhibit a liberal skew (Research 2018). Similarly, popular online sampling platforms such as MTurk have populations that are significantly more liberal than the US population (Huff and Tingley 2015)]. In such conditions, selecting left-wing charities as study stimuli is optimal. Alternatively, perhaps conservative charities do not reach out to academics for collaborations (or are less receptive to attempts) than are liberal charities: conservative charities are fewer in number, are more skeptical of academic collaborations, and/or may be less interested in academic research. Future research could, therefore, seek to empirically assess the extent to which conservative organizations and liberal organizations are differentially able and willing to collaborate with researchers.