Retributive Philanthropy

Prosocial behavior research has historically considered altruistic or self-interested motives as the primary drivers for charitable giving. Recently, however, there have been many high-profile cases wherein consumers use their donations to harm others. We define this behavior, characterized by a desire for retribution resulting from witnessing or experiencing volitional wrongdoing, as “retributive philanthropy” and examine this phenomenon using a multi-method approach. Qualitative interviews with perpetrators and targets of retributive philanthropy reveal key themes of blameworthiness judgments, strong negative affect, and a desire to harm as a terminal goal of donation—all of which are not typically associated with prosocial behaviors. Analysis of real-world anti-vaccine protestor donation data find similar themes of perceived wrongdoing and outrage related to retributive donations in a large-scale context. Five lab studies and five supplementary studies then demonstrate the effects of perceived volitional wrongdoing, harm, efficacy, and authoritarianism on willingness to make retributive donations. Together, these findings offer critical insight into an emerging mode of donation that is emotionally, motivationally, and behaviorally distinct from traditional prosocial behavior and has important implications for consumers and charitable marketers.

Prosocial Behavior, Donations, Consumer Aggression, Retribution

Introduction

“There’s one person who has a special place in our hearts: Mike Pence. Today, break his heart and make a donation in his name.” — Planned Parenthood (2021)

After Donald Trump’s election win in 2016, organizations concerned with environmental advocacy, women’s rights, and civil liberties received influxes of donations. Most notably, Planned Parenthood saw a 40-fold increase in donations in the months following the election (Preston 2017), an increase much larger than what other organizations experienced. What made Planned Parenthood different? It could be that donors believed abortion rights were uniquely threatened given the election of a conservative government. However, environmental protection and civil liberties were also at risk given the Trump platform yet did not realize the same increase. We propose the influx of donations to Planned Parenthood may be attributed to a set of donation motives and behaviors that are distinct from those typically investigated by prosocial behavior researchers. Post-election, consumers began donating to Planned Parenthood in Vice President Mike Pence’s name and using his real address (Mettler 2016), resulting in the Vice President receiving thousands of letters thanking him for supporting an organization he morally opposed. Upon recognizing this unique donation behavior, Planned Parenthood leveraged this phenomenon in its official advertisements, a strategic decision that led to over 82,000 consumers donating to the organization in Pence’s name (Ryan 2016).

This style of donation has recently expanded to multiple causes. For example, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, consumers donated to a Ukrainian NGO, “Sign my Rocket.” This organization encouraged consumers to inscribe personalized retributive messages on artillery shells to be shot at Russian soldiers in exchange for a donation to the NGO (Jankowicz 2022). Table 1 outlines further examples of this phenomenon. Importantly, these examples represent a diversity of political and moral viewpoints, and the punitive actions taken are provoked by situations representing a wide range of potential wrongdoing. Nevertheless, from the perspective of the donating consumers, all of these situations involve punishment of perceived wrongdoers through donation. These donations differ considerably from contemporary examples of prosocial behavior studied in extant marketing and consumer research and, we argue, constitute a novel form of charitable giving that we refer to as retributive philanthropy. Specifically, we define retributive philanthropy as charitable acts undertaken to punish a volitional wrongdoer. In our research, we seek to establish empirical support for this type of philanthropy as retribution, thus demonstrating the relevance of retribution to our theoretical understanding of prosocial behavior and generating practical insights for charitable organizations interested in leveraging retributive donations.

Our mixed methods approach includes qualitative interviews, analysis of real-world donation data, and lab experiments to investigate this distinct phenomenon. We demonstrate that retributive philanthropy requires perceptions of volitional wrongdoing, negative moral judgments, and a desire to punish. These findings sharply contrast with past research suggesting prosocial behavior is characterized by positive emotions like love (Cavanaugh et al. 2015) or gratitude (Bartlett and DeSteno 2006), positive relationships (Sepehri et al. 2021), and wanting to help others (Batson 2022). Although recent research and popular press opinion pieces have begun to discuss how rage or spite might motivate donations (Taylor and Miller-Stevens 2022; Witkowsky 2021), these dialogues do not consider how donations might be used as a vehicle for punishment, and as such are unlikely to be related to the antecedents (e.g., volitional wrongdoing), moderators (e.g., authoritarianism, efficacy at punishment) and mediators (e.g., negative moral judgments, desire to punish wrongdoers) that we investigate in our work. Retributive philanthropy, thus, represents a theoretical advance by expanding the range of situations, emotions, and motives that can drive prosocial behavior. In doing so, we answer Labroo and Goldsmith’s (2021) call for research that explores the “dirty underbelly” of prosocial behavior.

Substantively, we demonstrate the marketing relevance of retribution in prosocial contexts by exploring features of retributive appeals and retributive donors that could guide charitable marketers in their decision-making. Specifically, we demonstrate that volitional wrongdoing, the efficacy of punishing a wrongdoer, and authoritarianism make retributive donations more appealing to consumers. Collectively, our findings inform charitable marketers that retributive donation options have the potential to increase overall donations and attract new donors.

Conceptual Framework

Retributive Philanthropy is Prosocial Behavior

Contemporary work defines prosocial behavior as actions intended to benefit others or society at some cost to the self (Small and Cryder 2016; White et al. 2019). Based on this definition, we argue retributive philanthropy is prosocial behavior. All retributive cases in Table 1 involve consumers bearing a personal and financial cost through their donation to a cause that benefits a greater good. However, retributive philanthropy differs from traditional prosocial behavior in that it involves punishing others. Is such an ulterior motive consistent with prosociality? Indeed, a range of theoretically distinct ulterior motives have been identified as underpinning prosocial behavior (Batson 2022). For example, prior work has found that prosocial behavior is often motivated by a variety of self-interested aims, such as impression management, happiness, life satisfaction, and financial benefits (Curry et al. 2018; Hui et al. 2020; Kristofferson, White, and Peloza 2014; Peloza and Steel 2005). Whether an individual donates for a tax break or to look generous is immaterial to classifying the action as prosocial. Therefore, whether an individual donates to humiliate or otherwise harm another has no bearing on the prosocial nature of the donation itself. Nevertheless, some may argue that retributive philanthropy is morally distinct from self-interested donations by virtue of its harmful nature. On this view, harming others is immoral, and such acts should not be prosocial by definition. We contend this argument fails on three grounds. First, self-interested donations are considered by many to be immoral, insofar as the use of moral engagement for self-promotion corrodes public discourse, fosters political conflict, and is leveraged by individuals with undesirable personality traits like psychopathy and narcissism (Grubbs et al. 2019; Tosi and Warmke 2016). Yet self-interested donations are still treated as prosocial behavior in contemporary literature. Retributive philanthropy should be treated similarly as prosocial behavior that is driven, in part, by non-altruistic motives. Second, classifying behaviors in Table 1 as immoral fails to consider the individual beliefs, values, and expectations of donors, which are key to determining prosociality. To illustrate, consider two donors: one who donates to a pro-choice charity to protect the reproductive rights of women; one who donates to a pro-life charity to protect the rights of unborn children. Both donors believe they are doing good, despite representing mutually exclusive value systems. By the field’s standards, both are engaged in prosocial behavior, because they intend to do good, regardless of whether this “good” impact materializes or has negative consequences for others (Small and Cryder 2016; White et al. 2019). We argue this logic applies similarly to retributive philanthropy: from a retributive donor’s perspective, their motives are righteous, their actions are laudable, and punitive outcomes are desirable. Thus, to donors, retributive philanthropy is prosocial. Finally, retribution is frequently acknowledged as prosocial in adjacent fields of history, philosophy, and psychology. Recent work by feminist and political philosophers has stressed the importance of outrage, protest, and punishment as key factors in remedying injustices (Cherry 2021; van Doorn, Zeelenberg, and Breugelmans 2014). Retribution can also be prosocial, because it maintains valuable social norms and encourages cooperation (Jackson et al. 2019; Sommers 2022). Thus, we contend retributive philanthropy’s punitive component may also be prosocial.

H1: Prosocial behavior researchers will exhibit a preference for liberal stimuli.

Overview of Studies

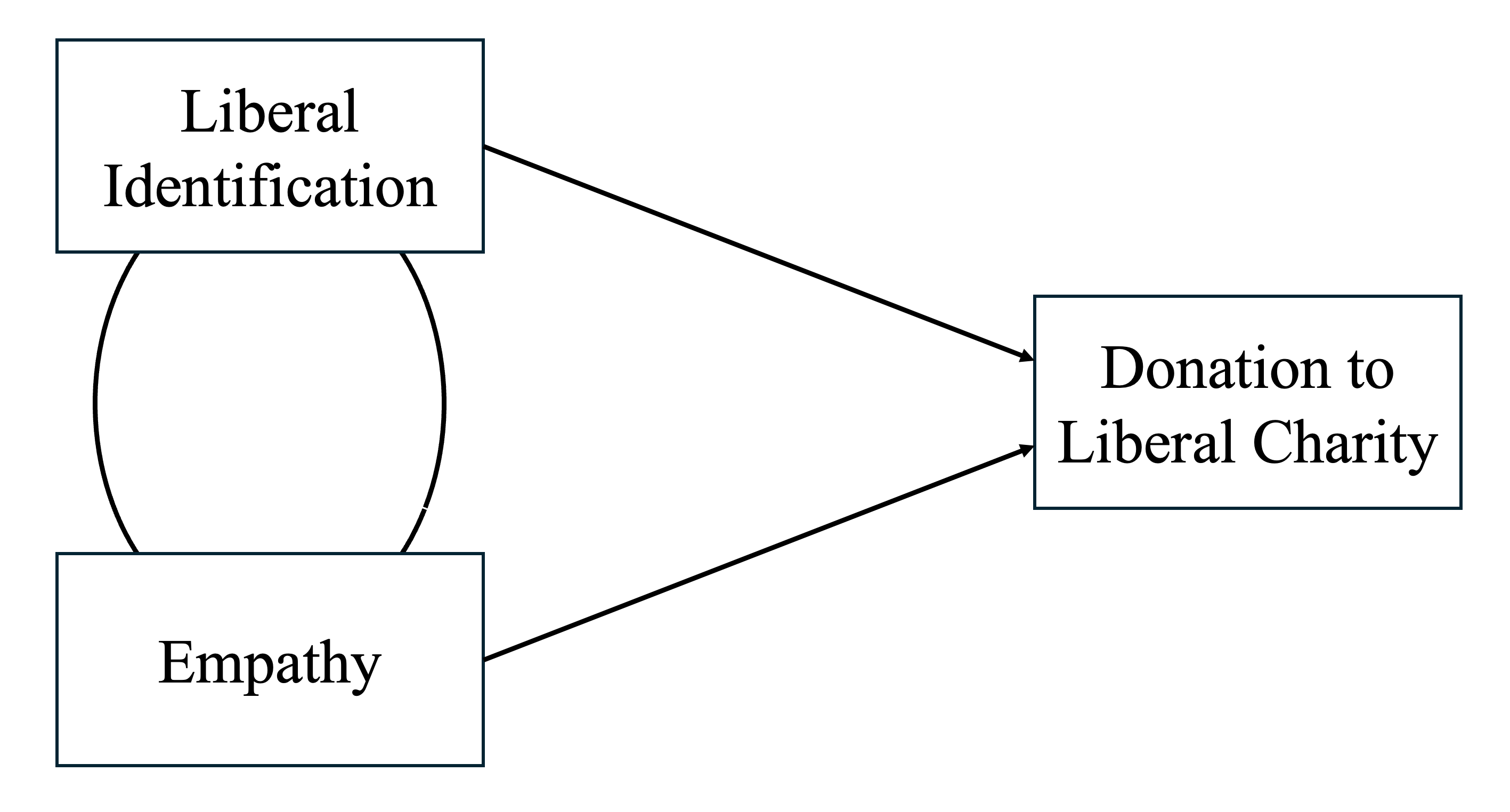

Using a multi-method approach, we present five studies that empirically investigate these hypotheses. In study 1, we tested whether contemporary prosocial consumer behavior stimuli exhibit a political skew (H1); whether religious cause areas were present among these stimuli (H3); and whether our hypothesized political skew could be explained by papers with higher stimuli counts (H4). In study 2, we surveyed prosocial consumer researchers to identify whether our hypothesized political skew could be explained by their political preferences (H2). In study 3, we demonstrate that the political valence of stimuli can serve as a hidden moderator for the effect of politically correlated individual differences on donation (H5). Finally, in studies 4a and 4b, we demonstrate that political ideology can confound analyses estimating the effect of politically correlated individual differences on politicized stimuli (H5).

Web Appendix

Web Appendix A: Study 1 Additional Information

Web Appendix B: Stimuli and Measures (All Studies)

References

Session Info

The analysis was done using the R Statistical language (v4.4.1; R Core Team, 2024) on macOS 15.2, using the packages epoxy (v1.0.0), quarto (v1.4), marginaleffects (v0.21.0), lubridate (v1.9.3), glue (v1.7.0), gt (v0.11.0), ggpubr (v0.6.0), parameters (v0.23.0), report (v0.5.9), here (v1.0.1), tibble (v3.2.1), gtsummary (v1.7.2), margins (v0.3.27), reshape2 (v1.4.4), ggplot2 (v3.5.1), forcats (v1.0.0), stringr (v1.5.1), tidyverse (v2.0.0), readxl (v1.4.3), dplyr (v1.1.4), purrr (v1.0.2), readr (v2.1.5), tidyr (v1.3.1), ggtext (v0.1.2) and knitr (v1.48).

- Aden-Buie G (2023). epoxy: String Interpolation for Documents, Reports and Apps. R package version 1.0.0, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=epoxy.

- Allaire J, Dervieux C (2024). quarto: R Interface to ‘Quarto’ Markdown Publishing System. R package version 1.4, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=quarto.

- Arel-Bundock V, Greifer N, Heiss A (Forthcoming). “How to Interpret Statistical Models Using marginaleffects in R and Python.” Journal of Statistical Software.

- Grolemund G, Wickham H (2011). “Dates and Times Made Easy with lubridate.” Journal of Statistical Software, 40(3), 1-25. https://www.jstatsoft.org/v40/i03/.

- Hester J, Bryan J (2024). glue: Interpreted String Literals. R package version 1.7.0, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=glue.

- Iannone R, Cheng J, Schloerke B, Hughes E, Lauer A, Seo J, Brevoort K, Roy O (2024). gt: Easily Create Presentation-Ready Display Tables. R package version 0.11.0, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gt.

- Kassambara A (2023). ggpubr: ‘ggplot2’ Based Publication Ready Plots. R package version 0.6.0, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggpubr.

- Lüdecke D, Ben-Shachar M, Patil I, Makowski D (2020). “Extracting, Computing and Exploring the Parameters of Statistical Models using R.” Journal of Open Source Software, 5(53), 2445. doi:10.21105/joss.02445 https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.02445.

- Makowski D, Lüdecke D, Patil I, Thériault R, Ben-Shachar M, Wiernik B (2023). “Automated Results Reporting as a Practical Tool to Improve Reproducibility and Methodological Best Practices Adoption.” CRAN. https://easystats.github.io/report/.

- Müller K (2020). here: A Simpler Way to Find Your Files. R package version 1.0.1, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=here.

- Müller K, Wickham H (2023). tibble: Simple Data Frames. R package version 3.2.1, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tibble.

- R Core Team (2024). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Sjoberg D, Whiting K, Curry M, Lavery J, Larmarange J (2021). “Reproducible Summary Tables with the gtsummary Package.” The R Journal, 13, 570-580. doi:10.32614/RJ-2021-053 https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2021-053, https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2021-053.

- Thomas J. Leeper (2024). margins: Marginal Effects for Model Objects. R package version 0.3.27.

- Wickham H (2007). “Reshaping Data with the reshape Package.” Journal of Statistical Software, 21(12), 1-20. http://www.jstatsoft.org/v21/i12/.

- Wickham H (2016). ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag New York. ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4, https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org.

- Wickham H (2023). forcats: Tools for Working with Categorical Variables (Factors). R package version 1.0.0, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=forcats.

- Wickham H (2023). stringr: Simple, Consistent Wrappers for Common String Operations. R package version 1.5.1, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=stringr.

- Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, Chang W, McGowan LD, François R, Grolemund G, Hayes A, Henry L, Hester J, Kuhn M, Pedersen TL, Miller E, Bache SM, Müller K, Ooms J, Robinson D, Seidel DP, Spinu V, Takahashi K, Vaughan D, Wilke C, Woo K, Yutani H (2019). “Welcome to the tidyverse.” Journal of Open Source Software, 4(43), 1686. doi:10.21105/joss.01686 https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.01686.

- Wickham H, Bryan J (2023). readxl: Read Excel Files. R package version 1.4.3, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=readxl.

- Wickham H, François R, Henry L, Müller K, Vaughan D (2023). dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. R package version 1.1.4, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr.

- Wickham H, Henry L (2023). purrr: Functional Programming Tools. R package version 1.0.2, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=purrr.

- Wickham H, Hester J, Bryan J (2024). readr: Read Rectangular Text Data. R package version 2.1.5, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=readr.

- Wickham H, Vaughan D, Girlich M (2024). tidyr: Tidy Messy Data. R package version 1.3.1, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tidyr.

- Wilke C, Wiernik B (2022). ggtext: Improved Text Rendering Support for ‘ggplot2’. R package version 0.1.2, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggtext.

- Xie Y (2024). knitr: A General-Purpose Package for Dynamic Report Generation in R. R package version 1.48, https://yihui.org/knitr/. Xie Y (2015). Dynamic Documents with R and knitr, 2nd edition. Chapman and Hall/CRC, Boca Raton, Florida. ISBN 978-1498716963, https://yihui.org/knitr/. Xie Y (2014). “knitr: A Comprehensive Tool for Reproducible Research in R.” In Stodden V, Leisch F, Peng RD (eds.), Implementing Reproducible Computational Research. Chapman and Hall/CRC. ISBN 978-1466561595.